|

Language and technology |

IntroductionThis guide is written for students who are following GCE Advanced level (AS and A2) syllabuses in English Language. This resource may also be of general interest to language students on university degree courses, trainee teachers and anyone with a general interest in language science. Please look at the contents page for a full list of specific guides on this site. What do the examiners say about this subject?Language and technology is one of the subjects studied within the broader area of Language and Social Contexts, which is set as a module for study within the specification for the AQA's Advanced Level (GCE AS and A2) Specification B for English Language. If you are a student taking this course, or a teacher giving support to such students, you may find the examiners' guidance helpful. But it may also be useful to anyone who wishes to understand how language relates to modern communication technologies. In giving guidance to people studying the subject, the examiners advise them to study: the variety of language forms insofar as they are affected by

In particular, the guidance says, candidates should examine

In their support materials the examiners add this: "For the purposes of [their assessment module] Language and Technology means language and communication technology… The focus is on how information and communication technology augments, constrains and simulates human-to-human communication…" The examiners suggest that candidates should consider:

The examiners note that academic research into this area of language use is still in its early stages, and that what is published may not be reliable. But at the same time, there is very wide use of the technologies of communication. For this reason, investigations of text messages and instant messenger conversations, carried out by students (perhaps for another assessment module) are as likely to be reliable as published books. There are more resources available for the study of (spoken) telephone conversations, radio phone-ins and sports commentaries - transcripts of which have appeared as data in examination papers on the current specification and the similar syllabus that preceded it. The examiners advise teachers to use varied types of text in presenting the subject. These might, for example, include:

The examiners provide some examples of questions, including texts of these types, with an expert commentary, and a preceding caution: that they are not to be taken as model questions. On the other hand, the commentary is a good indication of what an informed response would ideally include. A second caution stresses the need for balanced answers - general comment needs to be related to specific details in the texts, while attention to these specific details needs to be illuminated by reference to theory and general ideas about language that they exemplify or challenge. What is technology?"The medium is the message". Marshall McLuhan It's not necessary to start here, but in order to understand the connection of language and technology it may be helpful to arrive at a working description of what technology is. Here are some dictionary entries for technology: 1. Theoretical knowledge of industry and the industrial arts. These entries cover just over fifty years, and reveal a gradual change in meaning. The idea of arts drops out, while science is amplified to include science and computers. The Longman entry reflects the influence, perhaps, of the more specialized information technology. In this way, since the noun describes technology in practical use, its meaning now covers new or emerging kinds of technology. As a noun, therefore, technology does not denote a single, unchanging and specific thing. It denotes, rather, a very general category of things - which includes a very wide range of other things, some of which change over time. What remains constant is the idea that technology applies knowledge to achieve practical purposes. As regards language, while all technology has a connection to language use, this connection is arguably more explicit or obvious in the case of information technology. Here are two recent example dictionary entries for information technology: The study or use of electronic processes for gathering and storing information and making it available using computers. What does it have to do with language?All technology influences language, in ways that are not always obvious. The development of transport systems, for example, leads people to move around so that language forms used in regional varieties may move into other regions. We use a metaphor such as "all guns blazing" to suggest the idea of an action performed with energy or aggression - so the technology of weapons extends the usage of everyday speech or writing. Since technology is a means to extend man's reach, then it is necessarily connected to language, in the sense that both natural languages and technologies will be important in enabling us to do all sorts of things in almost any area of human activity. For example, we use aeroplanes to fly people and goods around the world. And we try to make this safer and more efficient by developing an air-traffic control system. That's language and technology working together for the common good. (And English is the language used in that system globally.) This uses one kind of technology (radio communication) to support use of language in conversations in an adapted form of international English, that pass on information derived from other technologies (radar, weather-forecasting systems), to the users of yet another set of technologies (the pilots of aircraft). This may help us to distinguish between the technology in itself, and the things we do with it, from a linguistic perspective. In terms of modelling our ideas about technology and language, we may think

Alternatively, we may think first of the kind of language interactions we make, and then of the technologies that enable this. In this kind of model, we might usefully think of

We may then find that particular technologies are designed for, and well suited to, some of these kinds of language use. And we may be less likely to make dismissive claims such as that the Internet is CB (citizen band) radio for the 1990s (as many cynical people once said). We will certainly find that the designers of the technology do not always anticipate the new kinds of language activity that will come from the ways that people use and adapt it. Think, for instance, of gramophone recording (a late 19th century technology) and text-messaging from and to mobile telephones (a late 20th century invention). Both of these developed in ways that their inventors did not foresee, but which we can now explain readily after having seen it happen.

Does technology make a difference to language use?Storing and transmitting information | Electronic text and digitized information | Instant communication across geographical space | Linking to other electronic texts and processes | Automatic recording of computer activity | Echoing previous genres and technologies | Challenging notions of fixity and authority | How technology influences new patterns of spelling and punctuation, and use of symbols In studying language and technology, you will look at how the technology influences the language use, but you should not assume that the use of technology to mediate the language necessarily changes everything. All kinds of circumstances can affect the way we use language. Using technology may do this - as we may note from the way that some speakers react to a journalist's microphone, or an invitation to leave a message on a telephone answering machine. But we should not suppose that, in the absence of such obvious technology, people speak in a neutral and "natural" way. Whereas in the past, some kinds of formal or rhetorical speaking were regarded as meritorious, and social conversation less well regarded, so now we can make the opposite mistake, and assume that spontaneous speaking of an unstructured kind, using many non-standard terms and constructions, is somehow more natural or authentic (and worthy of study) than more controlled or self-conscious utterance, using standard forms. Technology can allow us to eavesdrop on conversations legitimately, as when we listen to a radio or TV broadcast. It also allows us to read texts from a greater range of writers - where traditional publishing is more selective and exclusive. And it allows us to read writing that has not been regulated and corrected by editors to conform to standard orthography or house style. As with traditional publishing, where we do not know how many people have revised or edited the text that we eventually read, so also we cannot always know the process that has produced a text that we read or hear through a technological medium. We listen to a studio discussion on a radio broadcast, and picture the guests together - but do not realize that two of them are with the presenter in London, while a third is in a studio somewhere else. We listen to a conversation in a fly-on-the-wall documentary, and do not know how the effects of editing - of selection and omission - have changed it. Tim Shortis (Shortis, T., 2000, The Language of ICT, London, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-22275-3) suggests that the distinctive features of electronic text are that it:

Let's elaborate each of these suggestions. Storing and transmitting informationIt is easy to show objectively how technology has made it easier to store and transmit information - simply observing the number of documents generally, or of a specific type (say Web logs) on the World Wide Web demonstrates this. Likewise, it is an objective fact that a technology such as e-mail allows the instantaneous transmission of a large text document, with other kinds of data file attached to it, between any computers in the world that are connected to the Internet. And it is also an objective fact that the number of computers connected to the Internet (either occasionally or permanently) is also increasing. You can easily demonstrate this by conducting searches of the World Wide Web. In a split second, you will turn up thousands, maybe millions, of documents in which the search item occurs. I asked Google (http://www.google.com ) to search for "cat" - in 0.07 seconds it found 155 million documents in which this text string occurs. "Coffee" yields 52 million documents in 0.17 seconds. But one could never look at more than a tiny proportion of them all. Thus, the sheer volume of activity also challenges the user. In the Renaissance, it was possible for an educated person to know the titles and authors of most printed books in a given language, and perhaps to have read a sizeable proportion of them. The Bodleian Library in Oxford could aspire, through an agreement of 1610, to own a copy of every book published by the Stationers' Company - and for a while the librarians could still have an understanding of the complete contents of their shelves. But now, as a copyright library in the 21st century, the Bodleian receives some 1,500 volumes a week (75,000 a year). No individual can have more than an outline understanding of all of the extant printed texts. For every book that we know (a large number, perhaps) there are many thousands or more of lost, forgotten, hidden and unknown volumes. What is true of the production of print texts is equally true of digital texts - in trying to form a sense of the totality of such data, we can only make the most rudimentary and heavily qualified statements. Nor does the technology that keeps it extant temporarily, provide it with a permanent home: like the private letters and documents of individuals in past times, it is distributed among millions of digital storage devices. The very thing that enables us to store so much, and share it so swiftly, also makes these texts vulnerable to loss. An old book may survive for centuries but electronic storage is not so enduring. Indeed, digital publishing may have more in common with book production by manuscript in the ancient world - here texts were kept alive by a continual process of copying and distribution, replacing the old as they wore out, which for us may resemble the process of adapting information from one format or storage medium to a successor. Electronic text and digitized informationTim Shortis lists these together, but the first is of course only one of many examples of the second. In every case "digitized" information is really a series of 1s and 0s in the binary machine code that enables a computer or other device to represent the information in some other format, so that humans can experience it - such as an image (still or moving), a high-fidelity audio track or a text document that we can read, write or edit within the interface of a word processor, text editor or instant messenger. The technologist has found many ways to do more things because digital information can be used across a wider range of devices that are inexpensive to manufacture. (At an even more highly technical level, this is because these devices use principles of solid-state physics, so there are no moving parts.) Some of the most popular applications of digitized information are very closely modelled on analogue technologies - such as voice telephony, and TV and radio broadcasting (indeed the broadcasting bit of the process is not changed; the difference lies in the nature of what is broadcast - so now the same ultra-high frequency and very-high frequency radio waves carry signals that are decoded as digital information by the receiving device). Recording to CD, DVD, mp3 players and hard drives also mimics recording to audio and videotape. While Tim Shortis may be right to single out text as a most important language form that digital information can represent, I suggest that speech is not far behind. Information technology can convert any audio source into digital information (and reverse the process), so we can use this for

Increasingly the technology allows the end user to decide which of many possible interactions he or she will use. Over time, this enables the designer (without any need for expensive market research) to attend to improving the features people find most useful, and not to bother with those that people do not use so much. An example would be an Instant Messenger client program (a program that is installed on a computer or local device or storage area, from where it exchanges information with remote servers over a network - usually the public Internet). Such a program may have a facility for instant text chat, display of emoticons in the text, shared Web browsing (typing a recognized URL creates a live hyperlink), display of an environment, games and other tools (such as an area for shared drawing of pictures), a whiteboard (for shared presentations), application sharing, and sharing of live moving images over Web cams and of speech via microphones and speakers connected to an audio system in each user's computer. It is possible that someone might use all of these, but in reality most users limit themselves to the first and one or two others at most. On the other hand, this greater flexibility allows the technology to mimic more closely what happens in face-to-face meetings. I used to talk to you (in the same room), and show you some pictures in an album; now I chat to you (we are in different rooms) and send you the pictures (as data files) or point you to the document on the World Wide Web where they are displayed. Face to face, I might draw a diagram then pass it to you for you to add something (how you want to furnish a room or landscape your garden, say). The Instant Messenger allows us to do the same thing remotely. This may help refute a common misunderstanding among people who do not use computers - that the experience is socially impoverished, because so many elements of face-to-face meeting are missing. Increasingly, those other kinds of interaction, which might co-exist with speech, are available. But there are also new features that enrich the experience. We do not normally record spoken conversation (the presence of recording technology can inhibit our ability to speak in a way we regard as natural). But conversation in the form of Instant Messenger text produces a transcript that we can save (if we wish) or copy into other applications. Instant communication across geographical spaceTechnologies for instant communication over distances go back to the ancient world, and more recent times where heliography (using mirrors or lamps), semaphore and naval flags or loud musical instruments have been used for conveying orders and simple messages in battle. Technology has also served purposes for business in such differing areas as finance (where Edison's 1871 stock ticker used telegraphy to bring information to the New York Stock Exchange) and gambling (where radio and TV would broadcast horse races in betting shops). The Internet was originally developed as a resilient communications network for military purposes (resilient because it has so many nodes, and therefore possible routes from one point to another, that it would still work even if much of the network should be destroyed). So what is significant or distinctive about the instant communication provided by modern technologies?

Linking to other electronic texts and processesOperating systems | Application software | Data files and formats | Linking across platforms and technologies | Multitasking I suggest that the most significant difference for the individual user of digital information is that he or she can adapt, interact with, and generally control it in ways that were not readily possible with other kinds of information, or, indeed, where a manufacturer could prevent such interaction as a way of enforcing a copyright restriction. A second difference is that digital technology allows more interoperability - cine film and recording to a 45 rpm disc, for instance, cannot easily mix, but it is easy to record sounds in one digital format, images in another, and combine them to make a movie for playing back on a computer or other device. Let's think about that a bit more thoroughly. Traditional technologies (as in white goods like refrigerators and washing machines) rarely have any kind of interoperability. Many of them will be powered by a standard domestic electricity supply - but the fridge does not (yet) normally communicate with the cooker or the kettle*. *Since the turn of the 21st century, however, an Internet fridge has been available from several manufacturers. The Whirlpool Internet Fridge, for example, has these features, according to the manufacturer's Australian Web site:

Other technologies, especially electronic entertainment systems, have interoperability designed in. A hi-fi amplifier from 1974 could amplify an output from a CD player from 1994 because the latter used a standard kind of signal output and strength, as well as a standard kind of physical connection. Television receivers, DVD and HVS players and digiboxes for satellite TV reception all "talk" to each other (though the user can be challenged in setting up the connections and learning to use them together). The personal computer extends the idea of interoperability in an almost infinite direction. Competing manufacturers work to a standard design in which various components are interchangeable. The computer has a range of connection devices and systems that enable it to exchange information with other physical devices, such as printers, scanners, cameras, microphones, TV receivers, and many networking components (wireless access points, routers and switches), and thus, of course, other computers. But the interoperability goes way beyond that, to the software inside the computer. Beyond the basic input-output system (or bios) that tells the computer about itself when it "boots" up (the verb reflects the old metaphor of pulling oneself up by one's own bootstraps - an apparent impossibility which computer engineers have made a reality) - lie the operating software, the application software and the data files. Operating systemsThe operating system software (or OS) is the low-level software, which handles the interface to peripheral hardware, schedules tasks, allocates storage, and presents a default interface to the user when no application program is running. Most modern operating systems include a graphical user interface (GUI) as standard, so increasingly we include this in our idea of what an operating system is. Examples of operating systems would be Microsoft Windows and Linux (for PCs), Mac OS (for Apple Macintosh computers) and Solaris for Sun workstations. The user is often not aware of the operating system (except when confronted by the "Blue Screen of Death" - the nickname for the "Fatal exception error" message in the Windows 95 and 98 operating systems). But it is fundamental to the use of the computer to run specific applications, and for those applications to be able to do things together. (My word-processor can exchange live data with my spreadsheet application and my Web browser, only because they all share a global syntax within the operating system.) Application softwareThe modern personal computer (Apple Mac or Windows or Linux PC, say) began life as a relatively high-cost device for business productivity, as did many of the add-on devices we refer to collectively as peripherals - printers and scanners, for example. In a very short time the manufacturers' and resellers' competition for business customers made the price affordable for home users, which in turn influenced the development of the PC to include features for entertainment, and later for personal/social (not work-related) communication. The first computer applications were specifically intended for business activity. The spreadsheet (invented in 1979 by Dan Bricklin who never patented it) was largely responsible for the introduction of personal computers in many areas of business. Over time these applications have been adopted by users in other contexts, and adapted for such use. (So the spreadsheet becomes both a powerful tool for business users, with a high price tag, and a more customized tool for managing domestic accounts and paying bills, with a smaller price tag to match the customer's wallet or purse.) In the 21st century, the uses of office productivity software (spreadsheets, database management programs and word-processing) are widespread, almost universal, in business, commerce, education and administration. Increasingly for the domestic user the important applications are those used for leisure, entertainment and communication. This does not mean what are often loosely called "computer games" - which are a more defined and specific kind of application. Typically it may include, rather:

When we link digital information from one process to another, while using a computer, then we are almost certainly using one or more applications. Data files and formatsIf you use a computer, you will probably at some point have selected text or an image in an open document running in one application (a Web page, say, or a word-processed document), copied it, and pasted it into another document (in another application or the same one). You may not think how odd it is that you can do this, but from time to time you will be frustrated by not being able to do it. For example, you see some text in a document, try to copy it and find that you cannot. Among various possible reasons are these:

Really (for the very technically-minded) this is the same explanation in every case. The Flash movie does not use text but converts a text input into graphic information. The PDF file, likewise, seems to be text but is really a description of what a document (text or graphics or both) looks like so that a printer or monitor can display it to the user. Oh, yes, you say - so how come we can sometimes copy text from a portable document file, and then paste it into another application? The answer to that is that if a word-processed document is converted into the PDF format, then any text in the original is identified as such. This means that a reader program such as Adobe Reader is able to reverse the process by character recognition (more or less what happens in OCR software) and show the original text. If the original for the PDF is simply a facsimile copy (as when you scan a printed document, copy it and drop the result into a word-processor file as an image that fills the page) then the reader software will not be able to copy text, because strictly speaking there isn't any. It now really is a picture of the page. And you would not, either, be able to copy text from a word-processed document that really showed a picture of scanned text. If you can't follow this, don't worry. The point of this rather technical digression is to show how these are exceptions to a very widely honoured rule - that many designers of software use standard data formats (admittedly for their own convenience, because they can use character sets and screen fonts that are already designed). As a result, the user can often take information from one application and drop it into another, so that the applications become complementary. Where the process may require some adaptation there are often filters for importing or exporting the data where the user can customize the way the exchange will work. To take a very simple example, if we copy text from a document open in a Web browser, then as well as the text, we have a lot of information about its formatting (line breaks, font styles and sizes, and so on). In a word processor such as MS Word, if we paste the text, then much of this formatting information will be retained (with pleasing or annoying consequences, and certainly increasing the size of the resulting file). Alternatively we can choose a "paste special" option, and paste the text, and display it in ways that we can choose. For example, if we choose "unformatted text", then the result will be to show the copied text in whatever was the style of the passage into which we pasted it. Linking across platforms and technologiesDigital information is always intelligible, if one has the key. I could use a computer with a CD drive and a CD writer drive to make an exact copy of an audio CD, without the need for the copying computer to be able to play such CDs. (Usually it will be able to do this, but that's not the point; the point is that a suitable application could record an exact description of the digital information on the original, then burn it to the copy without going through the quite different process of translating the information into an audio output to be played in real time on the PC. If that seems either to be hard to follow, or blindingly obvious, then reflect on how long it takes to play a CD - it takes as long as the various tracks together, which may be more than an hour. But, depending, on the speed of your equipment, you may be able to make a copy in a few minutes.) It is possible to use technologies to translate audible speech into text and vice versa. These might seem to be tasks of comparable difficulty, but are in fact massively different. Text-to-speech is a robust, inexpensive and very accurate technology - the reader software typically

For any given text string there is a programmed audio output. The software does not have any way of determining emphasis, so produces exactly the same speech sounds (for each text string) in a monotone. Although a human listener would hear a representation of the text that he or she could understand (so that the text really resembles speech) from the point of view of the software (if I may be so anthropomorphic) the output is still produced by an interaction with a text file. Speech recognition software is more complex because it has to cope with massive individual variety in the speech sounds it sets out to interpret. For this reason, the user has to "train" it to recognize which text strings correspond to a given spoken output, and also has to learn some consistency in the spoken style of dictation. This means it is expensive, uses lots of system resources (many computers cannot cope with it) and still is haphazard unless the user spends a lot of time in training it. MultitaskingThe idea or promise of multitasking goes back to the early 1990s, when few personal computers had the system resources (mainly random access memory) needed to make it a possibility, without slowing down the activity of the various applications charged with the multiple tasks. Improvements in the performance and system resources of computers mean that it is now possible to run many applications and tasks at the same time. This greatly increases the possibility for what Tim Shortis calls "linking to other texts and processes". We can illustrate this by use of alternative scenarios, a decade apart, for achieving the same goal of preparing a piece of written coursework for assessment in an exam course. 1995 scenario

2005 scenario

This second scenario takes far longer to describe, but occupies less time, more efficiently, in reality. And the technology ensures that each process links to the others (mostly), while there are far fewer points (such as recalling lessons and making notes after the event) at which understanding can be lost in translation or transmission… However, the description shows that this approach is complex to understand (rather in the same way that the combination of things involved in driving a car is complex). For many people it is not intuitive, and they may prefer to use the old methods. While the potential saving of time is great, many learners and teachers may be reluctant to take the time they need to learn these new approaches. Or the student does not think of doing so, because he or she sees that the teacher will not be able to support this way of learning. As a result, the learning activities in many institutions become less homogeneous as some teachers use the new technologies coherently, while others use them selectively, or perhaps resist their use. Automatic recording of computer activityElectronic text, says Mr. Shortis, keeps a record of its history automatically. The user can choose to discard or delete it (though even then, many computer systems will keep a copy of the data from which that record can be restored, before a more permanent act of deletion). How does this work? In the case of electronic mail we can choose to keep copies of everything that we send and receive. For things that we receive we often have the further choice of keeping a copy on a local computer and leaving the message on the mail server (a computer connected to the Internet from which a client mail program brings the messages, as they arrive, to the user's computer or other device, such as a PDA). With text chat, in an instant messenger, the full conversation is stored temporarily in the messenger client window (the interface of the program that is showing the session to the user). When we finish the conversation we can choose to save it (usually as a text file) or discard it (though in this case, we may have set our user preferences for the software so that a copy is kept automatically in an archive for a specified period). This is not something that we can do with a spoken conversation. Interestingly, too, the user normally knows that the script of the conversation is retained in this way, but that seems not to inhibit the text messaging, as sound recording devices may do with spoken conversation. Not only that, because of the ability to link this with other processes one can use this automatic recording in various productive or creative ways. If one uses instant messaging to discuss some area of learning with an expert, then there is no need subsequently to make notes, beyond perhaps tidying up and formatting the text of the discussion. The same can also be true of e-mail exchanges. We can store the text as it is, or paste it into another document. Echoing previous genres and technologiesHow ICT texts retain or preserve features of older texts | How ICT texts differ from older texts How ICT texts retain or preserve features of older textsTim Shortis suggests that language use through information technology echoes previous genres and technologies. This is not really surprising, but to be expected. Human beings, faced with a new technology, may use it

At its most basic, this may be something as straightforward as publishing, on the World Wide Web, texts such as news reports, film reviews and recipes more or less equivalent to those found in print media, such as newspapers and magazines. These do not, in daily use, replace the print versions, but complement them - so, for example, I read today's report in a newspaper that I recycle; but if I want a report from last month, I can search an archive with a Web browser. Here are some less obvious examples.

How ICT texts differ from older textsHowever, behind this continuity lies an arguably more profound characteristic of new technologies:

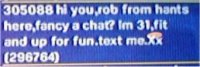

An example would be the mobile phone. This was developed to provide the benefits of voice telephony without the restrictions of physical location from which landline telephones suffer. In developing the physical device, the inventors used liquid crystal display technology to give the user assistance, for example in storing numbers and selecting people to call. Since the display was already attached to a telephone, the possibility of using the display to compose and send text messages would be self-evident. Tim Shortis suggests it was: "an afterthought; another gimmick to help beat the competition", but this is not substantiated, and does not make sense: while texting was an "afterthought" in the way that all refinements of systems are, the "competition" (all the service providers) adopted the use of the messaging universally, and it was not a gimmick but a serendipitous and obvious combined use of two technologies the mobile phone companies had already developed - sending data digitally and displaying text on the phone's LCD screen. With hindsight, it is easy to explain the popularity of the system - it is discreet (compared to spoken conversation) and inexpensive for the service provider (the sending of a message requires the user to be connected for only a split second, so the cost to the user can be set at a very low rate, and yet earn the service provider more income than voice calls, which require the user to be continuously connected). Hindsight can also explain some of the conventional abbreviations, acronyms and emoticons that enable the sender to keep messages within a limit of a set number of characters: currently (2005) for most services this is 160 Latin or 80 non-Latin characters. It is likely that developments in the SMS technology will allow longer messages in the future, although many users already work around this by sending multiple messages as part of a monologue or (more commonly, as the recipient replies) a dialogue. "Texting is free on my service, and even those who pay will usually pay less than for speaking mobile to mobile. Texting is also useful if you are in the London Underground and can't get any reception or are in a club and can't hear your phone. and if you want to send the same message to several people, texting is quicker than talking," explains Rachel Fletcher, 21. (Source: Nottingham Evening Post, cited on http://www.text.it) . Text messaging has some of the characteristics of spoken conversation (in its pragmatics and lexicon) and some of the characteristics of personal letters (in its pragmatics, again, in its register, and in its relative informality as regards grammar and orthography). But as a mode of communication it is not wholly like anything else. In looking at examples of text messaging in use, you may wish to separate

Challenging notions of fixity and authorityThe relative affordability of information and communication technology means that it brings power to the people. In earlier times various technologies were so expensive and conspicuous that the state could regulate their availability (whether for its own purposes, or for sale to wealthy businesses and individuals). That still happens in some ways, as national governments sell licences to providers of services and portion out the available wavelengths for radio and television broadcasts. The scenario predicted by George Orwell in his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty Four turns out to be profoundly mistaken. Orwell imagines a world in which a handful of totalitarian states keep their populations in poverty, engage in constant wars with no intention of defeating the enemy and, above all, seek to control not only people's actions, but also their very thoughts, by controlling all the print and broadcast media and technologies. Orwell supposes that the tendency of individuals to invent and adapt their uses of language can be suppressed, while a single state-sponsored set of language conventions ("Newspeak") establishes itself in everyone's usage. Orwell is wrong in his attitude to this kind of linguistic dissidence. Because it is not voluntary, it is not subject to control. Even under some dire threat, some human speakers will think and say unorthodox things, and many more will use language in non-standard ways, because they have a different understanding of grammar or of the lexicon from what is prescribed. He is even more wrong in his assumption that political states will continue to control the technologies of communication. While governments have been able to regulate print media and broadcasting to a point, they have not been able to prevent radio and TV signals crossing frontiers. Arguably, the Berlin Wall fell because East Germans compared their own government's accounts of the west with the evidence of western radio and TV broadcasting, which showed a more materially comfortable lifestyle and the opportunity for a diversity of opinions on political, moral and social questions. Internet technologies allow great scope to the individual to write or speak, publish or broadcast, read or listen. In many cases other people and organizations may try to restrict that scope. The restriction may come from

In spite of all of such restrictions, these technologies do generally promote change and allow individual expression in ways, and to an extent, that were not possible previously. Broadcasters and publishers are agents of change to an extent, as they allow new forms and new uses onto the airwaves and into print. But they also are agents of stability (or conservatism, depending on your attitude), in continuing to use forms that are regarded as standard in relatively formal contexts. We can exemplify this by noting that popular and informal speech may be heard on talk radio and phone-ins or on some youth programming on television, but that mainstream radio and TV news bulletins or documentary programmes use varieties of English that change more slowly. For many ICT texts, there is no explicit requirement to use any given conventions. Ideas of what is appropriate may be determined by an emerging popular consensus, but are no longer regulated at the outset by commercial publishers, editors and readers, as they have been in the past for most print texts. If I wish to publish a book, then I may be required to accept the policy of the publishing house in using, say, UK or US English. If I wish to publish a Web log or Web site, I can make my own choice as regards the language variety. Many new technologies allow individual and immediate production of texts (without the hindrance or luxury of a proof-reader or editor). Since the technology is still relatively new, it perhaps remains to be seen whether this will lead to a general relaxation of uses of standard forms. How technology influences new patterns of spelling and punctuation, and use of symbolsSome people (as any teacher knows) use non-standard ("incorrect" or "bad") spellings. There is nothing new in this - there is plenty of evidence to show that ever since Dr. Johnson and Noah Webster helped us to determine some standards, many real writers have neither known nor conformed to the standard spellings. What is perhaps different today is that texts containing non-standard spellings may be seen by far wider audiences. It may also be true that these audiences do not notice, or do notice but are not much bothered by, the non-standard forms - because they are more interested in the information or attitudes expressed in the text. The language student and scientist should guard against a popular (but illogical) tendency to find fault with the writing or speech of an individual, and then make this the basis of a claim that "English" is changing for the worse. That is objectively meaningless or nonsensical. It may be that a greater or less proportion of a given population (all the people in Britain, all 18-21 year olds in some university, all the fans of a popular singer or football club) do or do not use the standard spelling of "adviser" or know the conventional use of the dash. But that does not prevent any other person from writing with control and flair. Different technologies influence spelling in different ways. Spell-checking tools in application software enable the user to eliminate non-standard forms, though they do not show where a writer uses a standard form of a lexeme other than the one he or she intends. So, for instance, one finds increasingly commonly that "lead" (the present tense and infinitive form of the verb "to lead") is written in contexts requiring the past participle "led" (possibly by confusion with its homophone noun "lead", as in the heavy metal). It may be that reliance on these tools, too, leads some people to learn less for themselves about standard forms, in the same way that reliance on the calculator has apparently led some people to care less about mental arithmetic or learning multiplication tables. Modern word-processing tools allow a writer to use a specific variety of a language - so I can choose English with the standard spelling and grammar of Belize, Canada, Ireland, the UK or USA, for example, or exchange my preferred British orthography for one more suited to an international audience. Mobile phone texting, by contrast, promotes new forms. These typically abbreviate the standard form of a word or phrase - by such simple substitutions as numerals for syllables (be4, 2day, gr8). They also rely on the user's awareness of the conventions, which are often explained in user guides supplied with phones - an Orange mobile phone guide gives a table of abbreviations, including BCNU ("be seeing you"), F2T ("Free to talk"), PCM ("Please call me") and THX ("Thanks"). These short forms may be used playfully - they may use fewer characters than the standard equivalent, but sometimes the "saving" is of a single letter, so that the case for using the new form balances its possible unfamiliarity against the small economy achieved, as with 1daful ("wonderful") or WSUUUUU? ("What's up?") - this latter example reflects its association with a TV and cinema commercial (for Budweiser beer) where characters telephoned each other to ask this question, massively elongating the speech sounds. In many cases (echoing older forms) the text message uses abbreviations used in sending personal letters (SWALK="sealed with a loving kiss"; this form dates back at least to the 1950s) or in printed personal messages ("personals"), such as GSOH ("good salary own home" or, confusingly, "good sense of humour"). In studying language and technology, you should perhaps beware of a tendency in popular reporting and social commentary to exaggerate the importance of new technologies in influencing patterns of spelling. The new forms may be recorded in guides and glossaries, but you should look for any evidence that lexicographers are accepting them as standard. However, in 2004 some UK teachers of English language reported on an Internet mailing list discussion forum that they had observed text message forms appearing in their students' exam work. This is so far anecdotal evidence, and even if accurate does not yet reflect anything lasting or permanent. Many ICT tools make use of symbols (emoticons or "smileys") to suggest feelings and attitudes quickly. The smiling face image pre-dates the emergence of the personal computer, having been widely used as a badge or transfer for clothing in the 1960s and later. (It was adopted by evangelical Christians, with the slogan: "Smile, Jesus loves you", and more than a decade later associated with MDMA, the "recreational" drug popularly known as Ecstasy.) The importance of emoticons can be exaggerated. David Crystal claims that: "Very few of them are ever used. Surveys of email and chatgroups suggest that only about 10 per cent of messages actually use them, and then usually just the two basic types - :) and :( . Yet they still exercise a fascination: as an art form, or for entertainment." Crystal, D (2004), A Glossary of Netspeak and Textspeak, p. 119, Edinburgh, ISBN 0-7486-1982-8 I would qualify this. Instant messenger clients and some message boards allow the user to insert emoticons by a simple mouse click. These display as images (sometimes animated) in the client program or Web browser. Using these technologies with a wide range of contacts (both sexes and all ages from young children upwards) suggests that most users insert some emoticons, and in some interactions they frequently punctuate or conclude a sequence of text. They are appropriate where, in face-to-face conversation one would use a gesture or a touch. They are perhaps more commonly used in mixed and in all-female interactions, than in all-male social interactions. Janet Baker states that: "These graphical accents can add expressiveness, emotion and aesthetics to written discourse. Do these smiley faces at the end of messages provide the reader with an insight into the author or are they just annoying little punctuation marks that you have to strain your neck to see. Do people that use emoticons also use emotional language in their messages? And, do men and women use emoticons in the same way, and with the same frequency? It may be interesting to reflect that early forms of writing (pre-alphabetic) used pictorial symbols - whether pictograms (where a picture of an arrow represents an arrow) or ideograms (where a picture of an arrow represents war).

At the same time, users of the new technologies may be more conservative than is commonly supposed or reported. The following extract is summarised from an article by Kristen Philipkoski, entitled The Web Not the Death of Language. This was published on February 22nd 2005 at http://www.wired.com

Language and technology over timeThe history of technologies for writing | Typesetting and printing | Technologies for communicating remotely The history of language and technology is not as old as the history of language, but is exactly as old as the history of recorded language, which means at first the recording of language by the use of symbols - pictograms and ideograms. The history of technologies for writingIn the modern world we take for granted the availability of writing materials and implements. But just as writing has a history, so has the material used to transmit it. Some of the most ancient writing in the world that has survived today appears on large blocks of stone. This may be a suitable material for important documents that are meant to be permanent. But fairly early in the history of writing people looked for a way to make texts more portable. Around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers smooth river clay abounds. Between 4000 B.C. and 3500 B.C. the Sumerian people who lived in this region found a way to use this clay as a writing material. To start with, they used picture language, not unlike the writing of Egypt. Over time, in an evolution we can trace in surviving evidence, the Sumerians simplified their pictures into basic patterns of a few lines. The development of this basic writing was also determined by the technology used to make marks in the clay. This was a tool rather like a pencil but without a lead, and not sharpened. The writer would press a corner of the end into the clay, making a wedge-shaped line. The writers soon found that by combining five or six such lines or strokes, in a range of vertical and horizontal positions, they could produce a range of symbols to cover all objects and ideas about which they might want to write. For many purposes, however, clay and stone are not practical materials. Suppose one wants to be able to write down a long story, and keep it in a portable form - how can one do this using stone as a writing material? The solution to this problem came from another part of the ancient world, Egypt. The writing of Egypt, like that of the Sumerians, started as a picture language. Here, too, the pictures became stylized over time, but less so, because the Egyptians had a more flexible means of writing. Their writing material was papyrus, a kind of reed, which grows in marsh areas. The soft pith from inside the tough stems was cut into long strips. These were laid side by side to form a first layer, after which a second layer was laid on top, at right angles to the first. Both layers were pressed together, releasing a natural gum, which bonded the strips together to form paper sheets. These were glued together to form much longer sheets, which were rolled up for carrying. The writing implement used by the Egyptians was a reed, frayed at the end, to form a brush. Later, the Greeks would replace this with a split reed, forming a nib. The nib enables the writer to control a flow of ink to a finer point. The ink was a mixture of gum and a colouring agent - soot or lampblack. The scroll was to have a long history and spread far beyond Egypt. For the producer, which had a virtual monopoly of the commercial supply it was a valuable product for foreign trade. The Egyptians used the well-known hieroglyphics for writing on stone. They soon found that writing on paper could be swifter if they simplified the writing to a script. Carving on stone is easier using straight lines, but with a brush and paper, rounded strokes are possible. Apart from having to dip the pen in ink every so often the scribe could write continuously (rather as we do with modern pens). The writing on papyrus developed into a more rounded script in a style known as cursive (which means "running" in Latin). This form of writing also took its name from the hieros or priest and is called hieratic script. It marks a kind of transition in the development of writing, between hieroglyphic and alphabetic script. The Phoenicians are the people traditionally credited with the move to a system of characters to represent sounds, rather than whole words - in effect, an alphabet. This development meant that a fairly small number of symbols could be used, in combinations, to represent all the words in a spoken language. This was a step of genius, which some languages have never taken. From this point, it is possible to trace the evolution of different writing systems that use alphabets (again the name, "alphabet", comes from Greek). Papyrus was the most common material but from the earliest times when they wrote the books of the Law, the Hebrew scribes would also use leather. From about 200 B.C. onwards another material appeared - which was parchment. The skins of goats and calves were shaved, split, bleached, hammered and polished to form a smooth writing surface. This was a more expensive writing material than papyrus, but longer lasting. The first books were scrolls, up to thirty metres in length, formed by pasting together papyrus sheets. For reading, these were unrolled from one end, and rolled up from the other, to present a manageable portion of text to the reader. The Romans developed a different kind of book type. This was made of wooden tablets, coated with wax, in which the writer cut letters with a stylus. These tablets were bound with leather thongs that passed through holes in the wood. It is easy to see how this gave us our modern book form. The only big difference was that for many years these books were written entirely by hand - which is why they are called manuscripts. Typesetting and printingWhile writing has a long history, stretching over many hundreds of years, printing is a relatively recent invention. Printing with movable clay type appeared in China in the 9th century AD, but the western tradition, from which modern typesetting derives, begins in 1436 in Germany with the printing press of Johannes Gutenberg. This used replaceable wooden, and later metal, letters. At first these were limited in number, so that Gutenberg had to set up a page, print multiple copies, and then take it down, in order to set up the next page. In 1452 Gutenberg produced a printed version of the Latin Bible. Printing was at first an expensive way to produce books, and for many years after its invention more books were produced in manuscript (hand-copied) than printed form. Over several centuries the process became faster and more accurate. The greater availability of type eventually made it possible to leave pages set up. In the 19th century, Charles Dickens and others were able to publish novels serially in relatively cheap instalments - perhaps for the first time bringing substantial printed texts to a mass readership. Printing may be seen as having two important effects on language in the west.

There is, however, no single universal standard for spelling, as the Oxford and Cambridge University presses allowed some small differences (such as rules for "-ise" and "-ize"), while Noah Webster uses some variant forms that have become standard in modern US English. In contrast to modern computer-mediated publishing methods, the technology used to print books is expensive, and thus restricted to a few publishing houses. These publishers tended to be very careful in checking texts before they were produced in volume (reading what are called proofs), so that English printed books observe - and indirectly reinforce - use of standard forms, and also special varieties that differ from the language of everyday speech. Smaller and less expensive presses were in use for shorter texts, such as playbills or pamphlets, and here there may be more likelihood of non-standard forms. Until near the end of the 20th century, English publishing made a strong distinction between the publisher and the printer. The publisher determines the language forms, reading the printer's proofs and showing where they are to be altered, if incorrect. The publisher is also responsible for the content (and liable if it is treasonable or libellous). The typesetter and printer - seen as skilled artisans - are responsible for setting up the movable type, printing the pages, and, if need be, collating these and binding them together. In the 21st century, the publisher's role may seem little changed, but modern computer technologies have largely replaced the skilled work of the artisans, as the mass production of all printed texts is performed by machinery driven by information technologies. Technologies for communicating remotelyModern communication technologies have their antecedents in more limited systems that were developed for broadly similar aims - to overcome boundaries of distance or time. In some contexts, time is not critical - one can send a message, and allow for a delay. But there are some contexts where this is not possible. In the case of fighting a battle on land one can communicate information by showing a flag or standard, by use of devices that reflect natural light or that show artificial light (heliography). For more complex methods one can use pairs of flags displayed in different positions (semaphore). Until very recent times (well into the 20th century), for some kinds of communication the most reliable method was to send written notes carried by messengers on horseback, motorcycle or even on foot (usually young men who were fast runners). For battles at sea a complex system of signalling by use of flags was used until these were superseded by heliograph and radio. From the late 19th century onwards a related set of technologies developed, with the object of using physical devices to record or transmit natural speech. Recording technologies began with the phonograph, which evolved into the gramophone disc or record. Later came the use of magnetic tape, in the reel-to-reel and compact cassette recorders (as well as the short-lived four track and eight track cartridge formats). At the same time, radio found ways to convert physical sounds to electromagnetic waves, while telephony found ways to use the physical properties of sound to produce a variable electric current; the same variations, arriving in the receiver, cause a corresponding vibration which the user hears as an approximation of human speech. Beginning to study language and technologyIn some areas of language study, you may start with an open mind or blank sheet, because you think you do not know the subject. This may be the case with the early history of English or pragmatics, say. When you learn a little more, you may find, after all, that you did have some useful knowledge to start with. In the case of ICT texts, you may face the opposite danger. Because, in one way, you are very familiar with such texts both as author and audience, then you may expect to translate that familiarity easily into firm knowledge about how such texts work. As you begin, you should be ready to challenge any unsubstantiated assumptions - or at least look for supporting evidence and interpretation for any general claims that others make. Even where you see a convincing interpretation of a given ICT text, you may want to ask how far this text (and the interpretation of it) is typical of ICT texts generally. However, you should certainly begin by looking at some evidence. If you already have some ideas about what the evidence might show you, that is all right, so long as you are ready to accept a different view, if this is what the evidence does show you. How to acquire example textsSuitable texts | How to obtain texts In making a collection of ICT texts, you may wish to think about two quite different parts of your approach.

Let's take the second of these first, as it is arguably more important to the language student, and can be more briefly explained. Suitable textsIn one sense it is not only right, but also helpful in some kinds of investigation, to select a narrower range of language data from a wider collection. Very crudely, if I have a large collection of transcribed text messages, and if I wish to study the pragmatics of text messaging in mixed-sex exchanges, then I will use only those data where a male sends a message to a female recipient and vice versa. That is an appropriate principle of selection. But if I then reduce the selection further (to make it manageable), I need some way to make my selection as close as possible to being representative. If I already have a theory about what the data might show, then I must make quite sure that I do not select the data that seem most strongly to support my theory, and leave out the inconvenient texts. (As you study language science, you may find some examples of linguists who do this.) To avoid this, I could use some other way to reduce the total quantity, using some principle of sampling (say, by the name of the collector, the name of the source, or the date of collecting) that is representative of the whole. It is very easy to give more weight to the (selective) evidence that appears to prove a theory. A scientist may do this in good faith, honestly believing that contrary evidence is the exception that proves (confirms by testing) the rule. For example, you might listen to a post-match discussion on a TV or radio broadcast of a soccer game, and notice the supportive over-lapping and turn taking among the (male) speakers. You may have observed something like this on many occasions, but if you have already decided that men (generally) don't talk like that, while women do, then you may effectively use the available evidence to support a conclusion opposite to what it indicates directly. How to obtain textsFor many kinds of ICT text, obtaining them is as simple as copying data in a range of formats (either as complete data files, or as data objects, like text and images) and storing them on a computer or network. There are reasons why you may wish to have the same data saved in different ways - for example as unformatted plain text or as text and images formatted to preserve its appearance exactly as in its original context. Depending on the kind of investigation you intended to make one or other of these would be far more suitable than the other. For example, if I'm studying the writer's lexicon or syntax in some quantitative way, then I want plain text that I can analyse with various tools. If I'm studying the author's awareness of the audience in some qualitative way, then I will want to see how the text was presented to that audience originally. Texts from TV can be saved to various media, from VHS or DVD formats, to hard disk storage. Radio programmes can be saved in the same way, from satellite broadcasts, or converted to computer data files in formats like mp3 and Real Audio, using appropriate software. Alternatively, you can use broadcasts that are already saved and made available for use in this form. The BBC has begun to do this experimentally with some radio programmes available in mp3 format, while Teachers' TV has a range of short programmes for users to download. In each case, you will find the files on the Web sites at http://www.bbc.co.uk and http://www.teachers.tv. If you search the World Wide Web, you will find more such recorded programmes that you can download. It is possible to obtain text messages in a similar way, if you use Internet technologies to send or read them - a service that some networks or third parties provide. But if you send and read them using a mobile phone only, then you may need to transcribe them as a text or word-processor document. You should

Please note that while you would hold this information in a database or text document, you should have obtained the permission of the people concerned to do this, and would not pass on this information in unethical ways. (In an investigation you might refer to the sex or age of the sender or recipient, if this is relevant to your research; you would never identify either by name, but might use convenient initials.) There is more guidance on ethics below. Sharing the textsOnce you have a collection of documents as computer data files, then it is easy to share them with other people, and make larger collections. Copyright laws may limit the extent to which you can do this, and will normally prevent you from publishing your collection on a Web site. Of course, where the texts come from you and your friends (e-mail messages and texts, say), then you can share them as widely as you have all agreed to do. There may be some situations where you are unable to use computer technologies to study the texts, and where you resort to printing them onto paper. Some teachers may still rely on doing this and photocopying the printouts, but it is better (for interacting with the texts and for the environment) to do as much as possible in digital form - such as adding annotations, comments or highlighting. Using the textsWhile it is possible to obtain (for free) some simple tools for analysing electronic texts, you can make a start by using some of the features of a word processor. Take the example of a collection of transcribed text messages, using Microsoft Word. (Other word processors may have similar tools.) If these are already saved in a single document, that is fine. You need to delete any of the contextual information (and initiating and responding messages, if you do not need these). Ideally, so as not to lose the information you have deleted, save the resulting document with a new name. If they are not saved as a single document, copy the individual messages (without any of the other information) so that each is in a separate paragraph. Now you can use either the Word Count option on the Tools menu or the Properties option on the File menu. Either will show you the total numbers of pages, paragraphs, lines, words and characters (with and without spaces) in your document. Using a calculator or spreadsheet, you can now keep statistical records and perform calculations, such as the mean number of characters per paragraph. You can also use the Replace tool (on the Edit menu in MS Word) to replace a given character or text string, note the number of replacements shown, then undo the action. In this way you can calculate the frequency with which the various message writers use any lexeme. With spell checking and grammar checking you can identify and compute the frequency of use of non-standard forms. In MS Word, you can also set the spelling and grammar checker to show readability statistics. (To do this, go to the Tools menu, select Options, then choose the Spelling and Grammar tab, and make sure the box marked "Show readability statistics" is checked.) The software uses the Flesch Reading Ease and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level scores, as explained here.

Guidance on ethicsPermission to use language data - example letter of request In studying language and technology, you will normally wish to investigate ICT texts from a range of sources, including private individuals, such as your family, friends and students or teachers from your school or college. Sometimes this may seem intrusive, and it is important to respect other people, rather than see them as only a source of data. In general, you should obtain permission in advance to use these texts. And let people know what use you will, and will not, make of any data. Having said that, many people (your friends and acquaintances) may readily give specific or general permission for you to use texts that they have written - such as e-mail messages, mobile phone texts, text chat from instant messenger conversations, postings on message boards, and Web logs. If you are a student, you may wish to use these in relatively closed context - for your individual study of the texts, or a shared activity in a classroom. A teacher may wish to share them more widely, for example with other teachers, to build up a more extensive collection. It may be sensible, therefore, to get the explicit permission of the "owners", for any uses you may wish later to make. (Conversely, it is very frustrating to find yourself later unable to use data that you have painstakingly collected, because you omitted to get this permission.) Where you use such texts in any public context, then in most cases you should remove anything in the data that might identify any individual exactly. It's not acceptable to assume that you can take liberties because you know the person from whom you have acquired language data. You may wish to use the specimen permission form below. (Adapt it as necessary.) Permission to use language data - example letter of request

Considering the authors and the audiencesIn this guide, ICT texts are categorized by the technologies that are used to produce and experience them - telephony, radio and TV, and Internet technologies. We can, however, also usefully consider them in terms of number - is there one author or more, and is the audience an individual or a larger group? A second dimension would be the degree to which the contexts of utterance and reception are private or public. Let's explain each of these ideas further. A well-known 1990s commercial for a UK mobile phone company asked the question "Who would you like to have a one-to-one with?" Some kinds of ICT text are very clearly communications between two individuals (dyadic communications). When the participants are aware of each other as individuals, then this influences the way they speak, text or write. Examples would be

ICT texts may also come from one-to-many interactions, as happens when I

Where there are multiple authors, we can also see the interactions as being many to many, as happens when a number of people

In a way one-to-many and many-to-many interactions may overlap. The difference may lie with the author in the degree to which he or she feels a sense of being one among many speakers or message-posters, or is unaware of the others who contribute. We can think, too, of situations where two people speak to each other, but in the context of a radio or TV broadcast with a huge unseen external audience. The degree to which an ICT text is private or public is related to these questions, but has some further dimensions. A one-to-one conversation may be typically private, but this can change when, for example:

You can also see that in any of these cases, the degree to which any one person is aware of the privacy or openness of the communication varies. There are people who will speak on a train without making any concession to the presence of other people, while others will moderate their speech in all sorts of ways because the situation constrains or inhibits them in some way. In studying ICT texts, you should certainly consider these distinctions - which belong in the broader area of pragmatics. You should focus, especially, on the ways in which the technology has an influence on how they work. Sometimes this leads to quite novel kinds of interaction, as when someone sends a text message, knowing it will be displayed on a TV broadcast, where a wide audience sees it, some of whom may in turn respond, so that their replies are also displayed on the TV broadcast. InvestigationsIn any area of language study, it is often helpful to supplement what you read about other people's research by making your own investigations. This is a good idea because language in use changes over time and is influenced by many social and cultural factors, so that the findings of a particular piece of research may be valid for the place and time where it happened, but may not be as widely (or universally true) as is claimed. To give a simple example, anyone who watches and listens to the BBC's football programmes Match of the Day and Match of the Day Live will hear men speaking in ways that are supposedly more characteristic of women (turn-taking, supportive overlapping, positive feedback). In the case of ICT texts it is especially important for obvious reasons. The novelty of these forms of language production means that any research into it is necessarily limited - it will be recent, perhaps not widely published, and will not have had much time to be tested by other views, so that a consensus can emerge. Even where the research is good, it may need to be repeated frequently, because the uses of new technologies are themselves changing rapidly - so that, for example, the conventions that might characterize, say, the use of electronic mail for business communications have changed equally rapidly. (Because of spam, it is less efficient; the users are now more aware that it can be read by others for whom it was not intended - which may be anything from malicious forwarding to industrial espionage; a technologically sophisticated user may send only as plain text, because he or she knows that many mail browsers will not display rich text or HTML correctly, and so on). This means that your own research may be the best that is available - perhaps because it is done well, or perhaps because it is the only research that is available or that is relevant to the area of theory about which you wish to have objective information. Interactive textsSome kinds of digital text are described as interactive. This is, strictly, incorrect. No text, in isolation, can be interactive - interactions occur in the relationship of a text to its author and audience*. And when people are involved, any text can be used interactively - we can take a handwritten or print text (whether it's a poem or a piece of junk mail) and read it aloud, write a review, plagiarize it for some other text and so on. *One might quibble with this and say that there is one way in which a digital document can be interactive without human agency, since a search engine robot (also known as a spider or crawler) can perform an automatic cataloguing of the content of documents on a Web site, and send the results to the search engine database. However, this task has no value until a human being performs a search that uses the information that the robot has sent back to the database. Many of the interactions that may happen between a text and its audience will not be affected by the technology used to produce it. If we want to perform a scene from a play, we can use a printed copy of the script, or find a digital version, and use this to learn our lines. (In the case of a play, one might begin to perform with a printed version of one's lines and cues, but would be less likely to use a computer for this - though perhaps a handheld device or personal digital assistant would serve this purpose.) But there are some kinds of interaction that are specific to digital texts. These may be

As an example of the first, we can publish the text to an unlimited number of readers at no extra cost, whereas printed or written documents require more material and labour to produce multiple copies. In the second case, there are many things that we can do with conventional print texts, but which are so time-consuming and subject to the possibility of error, that we would not do them at all, or would do them, if we really needed to, very slowly. But we can do them easily and conveniently with suitable computer applications. Examples would be

There are some kinds of interaction that are more convenient using print texts. One can obtain the text of a novel as a digital document, and read it on a personal computer's display device. But most readers will find it easier to use a printed version in book format. The author of a digital document can also use some kinds of software to prevent interaction. If you prepare documents in some word-processor or portable document format writer software, you can fix the text so that the end user cannot copy it, replace it or save the document under a different name, for the purposes of editing it. However, readers with sensory impairment or some kinds of learning difficulty may be able to read the novel more easily in the digital format, since this allows the use of text-to-speech software and other reader devices. We can also use computer software to increase the size of the text as it is displayed (as the writer of this guide did in writing it, to overcome the effects of a temporary visual impairment). Social functions of technological mediaUse of computers for social interaction | Cyberspace as a social context Use of computers for social interactionSome people may regard interactions conducted in cyberspace as not social by definition. They challenge our understanding of the qualifier "social", because traditional social activities require people to be physically together. But personal relationships in an abstract sense, and intellectual exchanges can and do proliferate. This is found chiefly in the use of distributed networks (internal networks[Intranets] or the external Internet: Inter- here is short for "international" not "internal"). Visits to Web sites allow for limited interaction, but mostly this is a new form of reading, with little scope for response. More significant is chat. This is a metaphor from speech, but the interaction is conducted in writing (typing). As in spoken conversation, there is turn taking and contributions may be short. As in social conversation, standard forms are not essential - phrases replace sentences, there is no spell checking, punctuation may be "creative" and emoticons may appear. Some software allows the "chatters" to insert images, known as avatars, to represent themselves in the "conversation". These characters are conventional representations by sex, dress and age. Millions of such interactions take place daily, often bringing strangers together. Cyberspace as a social contextLike other social contexts, cyberspace has protocols and etiquette. For Internet technologies, this is usually called Netiquette. It is easy for a novice to send a mail message to millions of other users, or to ask a question to which the reply is already well known among other users of a service. So there are rules, and names for disapproved practices. Mail sent out en masse (electronic "junk mail") is called spam (the word is also used as a verb). Sending repeated severe verbal rebukes to those who breach Netiquette is flaming. Postal addresses are rarely exchanged (no need) and many users do not reveal their sex, or even, sometimes, their personal names - the e-mail address is an alias. Since each user may be at home, each may feel some intimacy in the interaction. Cost is minimal (compared to telephone calls) and while the exchange may be swifter than "snail mail" (conventional postal letters) there is enough time delay for responses to be composed. On Home Truths (BBC Radio 4, Jan 2nd, 1999) John Peel interviewed a young (British) man who claimed to have a cyber girlfriend. He was in Wales; she was in Central America. They exchanged messages by electronic chat and e-mail (and sometimes by telephone). They had no immediate plans to meet physically. This may be strange and unrepresentative of anything - or it may be a glimpse of the future! Representation of technology and languageComputer users as a group - cyber culture | Social attitudes to computer users Computer users as a group - cyber cultureTraditional groups, which are significant for language change, use or interaction, were necessarily located in a common place (region or locale) or class or peer groups. Computer users can meet without being physically close, or even aware of the location of other users. But they are identifiable as a group in their language use, in terms of lexical choice, language fashions and conventions and awareness of language. Younger users of Internet communications are serious multitaskers. Naomi Baron's 2003 study quoted above found that: