|

English varieties of the British Isles |

IntroductionThis guide is written for students who are following GCE Advanced level (AS and A2) syllabuses in English Language. This resource may also be of general interest to language students on university degree courses, trainee teachers and anyone with a general interest in language science. Please look at the contents page for a full list of specific guides on this site. The Assessment and Qualifications Alliance (AQA) has made this a subject for examination within a general area of study described as Language and Social Contexts. The AQA outlines the requirements for students taking this module in this way: In preparing this topic area candidates should study: the variety of regional forms in terms of accent, lexis and grammar; the social functions that dialects perform; the relationship between dialects and Standard English; historical and contemporary changes, where appropriate. In particular, they should examine

This guide will reflect the categories that the AQA examiners identify, but will look at English dialects more widely than appears in their description. What is dialect?It may be useful to begin by deciding what a dialect is. Dialect describes a language variety where a user's regional or social background appears in his or her use of vocabulary and grammar. This description is a very open one, and there is continuing debate about its application to particular varieties. Before considering these, it may help to explain the related feature of accent. (Some linguists include accent, along with lexis and grammar, as a feature of dialect.) Accent denotes the features of pronunciation (the speech sounds) that show regional or social identity (and arguably that of an individual, since one could have a personal and idiosyncratic accent). Problems with this descriptionSize | Politics and language varieties This description of dialect lacks precision and coherence. We can see these as problems, but reflecting on the reasons for them brings more understanding of what dialect means, and of why an exact definition is an impossibility. That is, any dialect is a generalization from the individual language use of a wider population. It comes from observation and perhaps some objective study. But we will not, if we stand outside St. Mary-le-Bow church in London, hear everyone around us speaking a uniform variety of English that matches a description of “Cockney”. We will, however, if we speak to a hundred people who have lived there for more than ten years, observe some common features of lexis, grammar and phonology that we would not find commonly used if we repeated the observation in Aberdeen, Hull or Plymouth. There is a more fundamental objection to the conventional description of dialect - and this is that all language is dialect, including Standard English. This was originally a regional dialect, but has become a prestige variety, favoured by the courts, government, the civil service, the officer class of the armed services and the elite universities. Moreover there is a prescriptive tradition in education and broadcasting that has formalised the status and prestige of both written and spoken standard English. Barrie Rhodes, of the Yorkshire Dialect Spciety, states this more bluntly: Increasingly, we have come to criticise the whole concept of dialect (and associated adjectives such as “traditional” and “regional”); we now subscribe more to the notion of idiolect in recognition of the fact that there are as many “dialects” as people. For instance, one of my friends in Norway uses the musical hall northern expression “Ee, by gum!” and so, increasingly, does her daughter. My friend says she picked up this expression from one of her mother's in-laws in Lancashire. SizeDoes a region or other social organization need to be of a given size in order to have a dialect - and if so, what is this? People from the south of England may speak of “Yorkshire dialect” (as Frances Hodgson-Burnett does in The Secret Garden). And there is a Yorkshire Dialect Society. But we might qualify this description by saying that really Yorkshire has a number of more local dialects, perhaps in one of the historic Ridings or centred around one of the big cities. Scots is a regional variety of English, spoken throughout Scotland, alongside Standard English. Some speakers may freely mix elements of Standard English (SE) and Scots, for example features of grammar that the speaker does not know are from one or the other. (These might include, say, the Scots use of past participle after needs or wants, where SE has present participle: Scots has “this wants done” where SE has “this wants doing”). But if Scots is the form of English widely spoken in Scotland is it then, perhaps, a language in its own right? So when does a dialect become a language? When a shepherd in Yorkshire's north-western Dales says, “If tha seeas a yow rigwelted, tha mun upskittle it”, is he speaking in a dialect or a separate (Anglo-Norse?) language? Politics and language varietyDeciding when a variety of a language may be considered a language in its own right is sometimes a matter of linguistic fact, but may also reflect political wishes. Welsh is clearly a distinct language (it is not intelligible, to speakers of any other language). In the same way Icelandic is not intelligible to speakers of related North Germanic languages, such as Swedish. Scots also does not have a standard system of spelling - there is no official body to endorse this. (Neither does English, of course). And until recently, it did not have its own national assembly, while official publications for Scotland came from the Scottish Office, a branch of Whitehall government. Norwegian (which perhaps has fewer speakers than Scots - some 5 million worldwide) is the official language of Norway (it has two varieties, Bokmål and Nynorsk). The Norwegian state, like France, determines acceptable forms through a learned body, the Språkråd. Scots today is arguably in the same position as Norwegian in 1814, when the country gained semi-independence, and its own parliament. But Swedish, Danish and Norwegian (both varieties) are mutually intelligible. The differences among them are perhaps no more profound than those between Standard English and Scots (of any Scottish region). Welsh is not a Germanic language, and is not the language most widely spoken in the whole of Wales (English is). But it is now established as one of two official languages in Wales. Official publications use both Welsh and English (Welsh appears first), while there are requirements for broadcasters to produce programming in Welsh. Perhaps the growing activity of government in Edinburgh will lead to the emergence of Scots as a separate language (in an official sense). But this has not happened yet. Dialect is all around youOf course, if we accept that all vernacular language varieties are in some sense dialects, then this is a truism or statement of the obvious. But it may help us stop thinking that dialect is something that other people do in big cities or remote dales, and that we are not dialect users, too. Some supposed dialects - especially urban ones - have attracted the attention of broadcasters or writers, in ways that have made them familiar to a wider public. That is we can put a name to their speakers, Cockneys and Scousers and Geordies. The effect of this can be unhelpful.

If you are a teacher or a student, then you can find resources for studying dialect very easily. There are very extensive materials that you can find on the World Wide Web, for dialects that are not local to you. But you can find much more by staying at home - by reading, or listening to, the language of the people who live and work there, perhaps older people or those in historic and traditional occupations. (Or those who have time to talk about occupations that are no longer practised.) You can very easily gather, share and publish data, using digital recording devices (such as mp3 players/voice recorders) or computers with multimedia functions, and suitable recording software such as Audacity (which records mp3 files) or Helix Producer Basic (which records Real Audio files). LexisThe lexis of dialects is perhaps their most conspicuous feature for listeners and readers. (If we see unfamiliar grammatical forms, we may be able to infer meaning readily; but if we see a novel lexeme we can at best guess its meaning from the context.) This will include both forms that are peculiar to the dialect and forms that are found elsewhere, but have a distinctive meaning in the dialect. So beer-off for an off-licence is a distinctive form (found in East Yorkshire), while happen is a verb in Standard English, but in some Yorkshire dialects is used as an adverb, in the sense of “maybe” or “perhaps”, corresponding to Shakespeare's haply. (For example, “Happen it may rain tomorrow”.) There is no initial /h/ sound, so in dialect the written form may be given as appen. The common written representation 'appen implies mistakenly that the speaker has dropped a sound that was never there in the first place. While in Standard English indicates simultaneous time. But in East and West Yorkshire dialect it has the sense expressed by “until” in Standard English. Speaking on BBC Radio 4's Home Truths (Saturday 24th January 2004) the wife of a member of the Spurn lifeboat crew said of her husband and his colleagues: “A lot of men go out in the morning. They don't get back while seven o'clock at night... ” GrammarDistinctive grammar in dialects may be harder to detect or explain than distinctive lexis.

The social functions of dialectsAre there language interactions where dialect forms work differently from Standard English? In the past some speakers might have known only to use a dialect, but today many are aware of both dialect and Standard equivalents - so may use one or the other more or less in different social contexts. This may for purposes of greater or less formality or intimacy; and it may be conscious or involuntary (as when a speaker assimilates his or her style to that of another). It is worth considering how far dialect is determined by geography and historical accident, and how far it may be related to sociolinguistics. (For example, it may be that geography and historical isolation explains the origin of a dialect, but that social attitudes explain its survival.) The primary social function of any dialect (or of all language) is communication, but there are also claims to status and identity that are bound up with the choices of variant forms. However, the emergence of a prestige variety of Standard English is largely a series of accidents. Had Alfred (king of the West Saxons) not defeated the Viking Guthrum at the Battle of Edington, then York might have been established as the capital of England, and the Standard English of today might have been an Anglo-Norse variety. Of course, that did not happen. Dialects and Standard EnglishWithout the notion of Standard English, we may find it hard to identify anything as a dialect at all - since the distinctiveness of a dialect consists in those things that are different from the Standard. (This does not mean that a dialect emerged from people who took Standard English and then changed it; it is more likely that the standard variety and the dialect variety developed from some common and some locally distinctive influences over time, or that the dialect forms are older, and have been more resistant to tendencies to converge towards a standard variety.) There is a problem in identifying any dialect as the standard, since this implies that other dialects are inferior or wrong. In the case of spoken English, we have good evidence that such prejudice exists - so there is an exaggerated danger that, in referring to a standard, we will strengthen what is already a tyranny. It may help to note that Standard English, too, is a dialect - albeit one that is no longer found in any one region of Britain. Barrie Rhodes notes: This is what has been termed "...the tyrrany of the standard" which gives the impression that there is something called "English" and all other varieties are, somehow, degraded, deficient, "incorrect" forms of this. [The idea of convergence towards this standard] for me, reinforces the impression that there is some set-in-stone ideal towards which people should strive. Some observers would claim that this is what made people uncomfortable and ashamed of their native speech modes...The notion is very strong and well established that there is something called "English"...And everything else is a deviation from this, arrived at through ignorance of the "proper" form. When I give talks to various groups, I find the biggest challenge is to get people to accept that there are many Englishes, all with an equal and valid claim to be "proper" within their own contexts. Only historical and geographical accidents brought prestige to what today we call the standard. But students could usefully ask (within a sociolinguistic paradigm) why people still choose to use non-standard speech when "...they should know better". My paternal grandmother...heard on the radio, understood and wrote Standard English (very well) - but she never spoke it. Had she done so, she would have soon found herself socially distanced from the close "West Riding" speaking community she lived in. There are all sorts of identity and self-esteem issues here that are worth investigating. The "standard" is a human choice that could have been otherwise (like driving on the right or left). It is not in any intrinsic way better or worse than other dialects. Nor are the historic regional dialects corrupt variants. Indeed, in many cases they preserve far older lexis, meanings or grammar than the so-called standard. Historical and contemporary changesIn studying dialect forms, as they exist now, you should be aware of the history behind them. Regional varieties of English have historical causes that may go as far back as the Old English period. They may embody or reflect much of the history of the places where they are used. Language is not a uniform and unchanging system of communication. It varies with place and changes over time. For example, human beings are capable (physically) of a wider range of speech sounds than any one speaker ever uses. Each language in its spoken standard forms has its own range of speech sounds, while regional varieties may leave out some of these and add others. Welsh has a distinctive sound represented in spelling by ll (voiceless unilateral l, common in place names). Some English speakers use post-vocalic r (rhoticization), though this is not common outside the north, Scotland and the south-west. The social history of any region often explains the language variety that has arisen there. York was the heart of the Danelaw, the Viking kingdom in Britain. To this day, the lexicon of dialect speakers in the North and East Ridings of Yorkshire retains many words that derive from Old Norse. Scandinavian influence on the language does not stop with the end of the Danelaw, however: in the 19th and 20th centuries maritime trade and commerce in the North Sea and the Baltic brought many Danes, Norwegians and Swedes to ports like Hull and Newcastle. The West Riding also has a large corpus of words of Old Norse origin. The Norwegian influence is stronger here, whereas Danish is more influential in the East Riding - there are more "Norwegian" forms than the "Danish" of, say, the East Riding. There is a historical explanation in the trade routes from Dublin, via the north-west coast of England, over the Pennine uplands to York, capital of the Danelaw. We see an illustration of this in the place-name ending -thwaite, of Norwegian origin, which is common in West Yorkshire, Lancashire and the Lake District, but rare east of the Pennines, where the Danish cognate -thorpe is far more common. Over many centuries, regional varieties retained distinctive lexis, grammar and speech sounds, because most speakers stayed in the place where they grew up, or near to it. In the late 20th century greater social and geographical mobility, combined with the influence of film and broadcast media, has altered the way varieties develop. Geographical location still exerts an influence, but it is not the only one. So, for example, British people of Asian descent, living in Bradford may speak a variety of English, which has West Yorkshire and Asian speech sounds, as well as those of Received Pronunciation, and a lexicon based on standard English with neologisms from the languages of the Indian sub-continent, and perhaps a few traditional Yorkshire dialect words. Social factors affecting variations within dialectsPeter Trudgill - gender, social class and speech sounds | Barrie Rhodes' research in the West Riding Do dialect forms have any relation to social attitudes? William Labov's study of language use on the Massachusetts island of Martha's Vineyard suggests that they do. Labov linked this use to subjective attitudes and showed that variation was not random, but correlated with age, attitude and social situation. One social factor that affects variation within dialects is the sex of a speaker - where women will be more likely to use forms that are seen as correct, while men will often choose to use a non-standard form and seek the covert prestige of resisting the ideas of respectability associated with Standard English. This is one possible explanation of the findings of Peter Trudgill in research in Norwich. In the late 1970s Trudgill interviewed people, whom he categorized by their social class and sex. He observed a number of variables against this (say the use of a particular speech sound in pronouncing a specific word) and recorded the data. Peter Trudgill - gender, social class and speech soundsPeter Trudgill's 1970s research into language and social class showed some interesting differences between men and women. This research is described in various studies and often quoted in language teaching textbooks. You can find more in Professor Trudgill's Social Differentiation in Norwich (1974, Cambridge University Press) and various subsequent works on dialect. Trudgill made a detailed study in which subjects were grouped by social class and sex. He invited them to speak in a variety of situations, before asking them to read a passage that contained words where the speaker might use one or other of two speech sounds. An example would be verbs ending in -ing, where Trudgill wanted to see whether the speaker dropped the final g and pronounced this as -in'. In phonetic terms, Trudgill observed whether, in, for example, the final sound of singing, the speaker used the alveolar consonant /n/ or the velar consonant /ŋ/. (Note: you will only see the phonetic symbols if you have the Lucida Sans Unicode font installed and if your computer system and browser support display of this font.) Trudgill found that men were less likely and women more likely to use the prestige pronunciation of certain speech sounds. It appeared that, in aiming for higher prestige (above that of their observed social class) the women tended towards hypercorrectness. The men would often use a low prestige pronunciation - thereby seeking covert (hidden) prestige by appearing "tough" or "down to earth". This is a plausible explanation of the results that Trudgill reported. But there may be others. Further observation may tend to support Trudgill's explanation, but with some further qualifications. Trudgill followed up the direct observation by asking his subjects about their speech. This supported the view of men as more secure or less socially aspirational. The men claimed to use lower prestige forms even more than the observation showed they really did. Women, too, claimed to use high prestige forms more than they were observed to do. This may be a case of objective evidence supporting a traditional view of women as being more likely to have social class aspirations than men. But it may also be that, as social rŰles change, this may become less common - as women can gain prestige through work or other activities. Trudgill's observations are quite easy to replicate - you could do so as part of language research or a language investigation. The value of this research is considerable.

Moreover, you can then think of further research that you could carry out, to see if Peter Trudgill's findings (from Norwich) would be repeated in other places. Barrie Rhodes' research in the West RidingBarrie Rhodes (in an unpublished research paper from 1998) suggests that generalisations about sex, age and social differentiation in non-standard speech may sometimes need to be re-evaluated along locally-specific, historical, occupational, socio-economic and lexical choice dimensions. He argues that, in the West Yorkshire community he researched, social networks influenced by changes in the once dominant textile industry have had a particular effect, especially on women's speech. Sex-differentiated speech he found to be less predictable than is sometimes claimed; in this study the youngest females emerged as proportionately significant conservers and users of the non-standard lexicon. Knowledge and use of non-standard words amongst some age/sex groups was shown to rise rather than fall with increasing social status. A lexical analysis revealed a matrix of differential trends and patterns in non-standard word knowledge and use; attrition appeared to be not simply a quantitative function but to be lexically selective in a complex way. Barrie Rhodes elaborates on some of these factors: ...I feel it is important to distinguish between "knowledge" and "use" of the dialect lexicon...in a West Yorkshire community, the substantially greatest knowledge was vested in women over 50 years of age - and they had also been the greatest users in the past. However, men in the 40-59 year old category were today's greatest users - though their level of use was markedly less than the older women's had been in the past. Furthermore, today's younger women (in the under 20 year-old category) were superior in both knowledge and use than their male peers. I was able to account for this variation from the "classic" view by showing that local social, occupational and economic history and modern dynamic developments need to be brought into the equation. Barrie Rhodes says that he does not see his study as contradicting Peter Trudgill's pioneering work. But by changing the focus somewhat, he has perhaps suggested the importance of some social factors with which Trudgill's Norwich study was not concerned. It appears that we cannot say that either men or women are, on the whole, more likely to use a traditional or archaic dialect form - sex is one factor among many, and there are reasons why both men and women, in different contexts and for different reasons, will conserve or drop features of traditional regional language varieties. Representations of dialect in writingSome of the earliest representations are found in literary works. Novelists such as Emily Brontë, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy and D.H. Lawrence all depict speakers of dialect, in ways that show their grammar, lexis and accent. In the case of some dialects, we have more than one representation - so we can compare Hardy's rustics with the poems of William Barnes (who wrote in a Dorset dialect). Here is a fairly early example, from the second chapter of Wuthering Heights (1847), in which the servant Joseph refuses to admit Mr. Lockwood into the house: " 'T' maister's dahn I't' fowld. Goa rahnd by the end ut' laith, if yah went to spake tull him" Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) has a similar approach in his poem, Northern Farmer, Old Style: "What atta stannin' theer fur, and doesn' bring me the aäle? Joseph comes from what is now West Yorkshire, while Tennyson's farmer is supposedly from the north of Lincolnshire. Here is an earlier example, from Walter Scott's Heart of Midlothian (1830), which shows some phonetic qualities of the lowlands Scots accent. In this passage the Laird of Dumbiedikes (from the country near Edinburgh) is on his deathbed. He advises his son about how to take his drink: "My father tauld me sae forty years sin', but I never fand time to mind him. - Jock, ne'er drink brandy in the morning, it files the stamach sair..." George Bernard Shaw, in Pygmalion (1914), uses one phonetic character (/ə/ - schwa) in his attempt to represent the accent of Eliza Doolittle, a Cockney flower girl: "There's menners f' yer! Tə-oo banches o voylets trod into the mad...Will ye-oo py me f'them." However, after a few sentences of phonetic dialogue, Shaw reverts to standard spelling, noting: "Here, with apologies, this desperate attempt to represent her dialect without a phonetic alphabet must be abandoned as unintelligible outside London". The pioneering work in linguistics of the brothers Grimm led to a more scientific approach - and a great bout of activity as researchers began to make records of regional dialects. The emergence of a phonetic alphabet enabled researchers to produce accurate transcriptions of speech sounds. Dialects do not normally have a standard spelling system. If one wishes to represent dialect in a way that shows the speech sounds, then use of phonetic transcription would be helpful. (The alternative is the kind of invented "phonetic" spelling that one sees in D.H. Lawrence: " 'Asna 'e come whoam yit?" - which is still common in literary works.) For some kinds of study (where the focus is not on speech sounds), an approximation to Standard English forms is acceptable. Thus the Yorkshire adverb happen (=maybe) sometimes appears in the same written form as the Standard English verb to happen - even if we know that for some speakers the dialect word begins with the [æ] vowel. (Barrie Rhodes suggests that we should write it as appen, since there is no initial consonant for Yorkshire dialect speakers; the use of an apostrophe, as in 'appen, suggests that the dialect form is somehow a mistaken or inferior variation of happen, even though appen is a different part of speech [adverb, where happen, in Standard English, is a verb] in the lexicon of the regional variety. There are some modern authors who write novels, using (for dialogue alone, or both narrative and dialogue) an approximate transcription of a regional variety of English or a creole, and this tendency is widespread in published poetry (which sometimes indicates the speech sounds used by the poet in performance). For an example of the former, consider this extract from James Kelman's 1994 novel How Late It Was, How Late, which is written in modern Scots: They shook hands. The narrative also uses this variety of English - in this passage of dialogue we note the regional lexis (wee, footery, didnay, wouldnay) or variant meanings for standard lexis (away), as well as a representation of the Scots speech sounds (fayther's, naw, and perhaps Boab, of which the usual spelling is “Bob”). In Sozaboy the Nigerian author Ken Saro-Wiwa explains that it is written in "rotten English" - this is "a mixture of Nigerian pidgin English, broken English and occasional flashes of good, even idiomatic English." Some of the poems of James Berry, John Agard and Linton Kwesi Johnson resemble transcripts, using a simple "phonetic" representation, of urban black English varieties or Caribbean creoles. Here is an excerpt from one of Mr. Johnson's poems, Di Anfinish Revalueshan: soh mi a beg yu mistah man It is as well to remember that these are literary examples - otherwise one may find people claiming these writers as the authentic voices of Black Britain (as if this were one uniform thing), or moving from an evaluation of the merits of the verse as art, and political comment, to its quality as a representation of the speech of a community. (In a symbolic sense, it may well be taken as representative, but we would need to see a lot more evidence, as linguists, before we could draw any conclusions about how typical or widespread this is as any kind of scientific or descriptive representation of the everyday speech of people in any part of Britain. In the same way, we would not readily accept the rustic characters in Thomas Hardy's novels as an objective representation of the speech of Dorset in the mid to late 19th century.) In the past, publishers and broadcasters may have silenced or excluded such voices. Nowadays they can find an outlet an an audience. While this gives expression to a greater diversity of language varieties, it may cause us now to undervalue those who use regional varieties that approximate more closely to standard forms. You may also see comical pseudo-phonetic or punning transcriptions to illustrate regional accent - on the analogy of a 1965 guide to Australian English, Let Stalk Strine (Let's Talk Australian), by Afferbeck Lauder (a pseudonym of Alistair Morrison. Graham Davies supplies this example of Lauder's “Strine” Consider the following transcript of a conversation between two Australians: A series of postcards entitled Learn to Speak Hull, Speak More Hull! and Speak Hull Again! contains "transcriptions" such as "fern curls" (phone calls) along with glosses - for "fern curls" it is "telecommunications". So we find, among others:

Most of these examples exploit the peculiarity of a vowel /ɜ:/ used by speakers in Hull and some parts of the East Riding. Film and TV dramaDramatists who write for film and TV (or the stage) may attempt to show the lexis and grammar of a dialect speaker, but their work is not authentic data in illustrating dialect in live use. (It may be instructive and worthy of study for other reasons.) And actors are not typical speakers - they are highly trained in the physical articulation of speech sounds, which they articulate with greater clarity (by exaggeration, distortion and amplification of speech as it might naturally occur). Film studios often employ special voice coaches (who may be expert phonologists) to assist performers in learning a regional accent, in a work where naturalistic authenticity is important. By comparing apparently inauthentic and authentic film accents, we may learn something about the real-life original. Barrie Rhodes notes of some popular TV dramas: Take Heartbeat - it is supposed to be set on the North York Moors, just a few miles inland from Whitby. Yet the characters tend to use a sort of generic "Yorkshire" accent that has more to do with Leeds/Bradford (if anywhere) than where the series is supposed to be set. In Emmerdale, there is more “Lancashire” (and south-eastern England) accent in evidence than “Yorkshire Dales”. And if you're going to have actors try to speak “Yorkshire”, at least make sure they can properly glottal stop the definite article - it's a dead giveaway! To be fair, few such dramas aspire to local authenticity - and there are probably as many offending examples of generalized London speech in film and TV, as there are false northern accents. From the language students' point of view, the value of such dramas as evidence for genuine local or regional speech sounds and language forms is nil. But they do have value as evidence of people's mistaken or inexact ideas about speech sounds and language forms that they do not know. If you want to study speech sounds in Peckham, you have to listen to the natives, not the cast of Only Fools and Horses. Regional varieties and non-regional varietiesPaul Kerswill and others contrast traditional dialects with modern dialects. The traditional dialects are varieties spoken by people in a given geographical area - in this sense we can regard the speech of the Black Country, East Yorkshire or Cardiff as a traditional, regional dialect. The modern dialects are varieties spoken in urban areas. Kerswill notes two contrasting tendencies at work.

Dialect levellingKerswill argues that there is a levelling process, whereby the modern or urban dialects over time move closer to spoken standard English, while retaining their own distinctive forms. He explains dialect levelling thus: British English in the 20th century has been characterised by dialect levelling and standardisation. It is probably useful to see this as composed of two stages, running in parallel. The first stage affects the traditional rural dialects of the country, once of course spoken by a majority of the population, but by the beginning of the 20th century probably spoken by under 50%. These dialects are very different from standard English in their pronunciation and in their grammar. What has happened is that, over one or more generations, families have abandoned these dialects in favour of a type of English that is more like the urban speech of the local town or city. These more urban ways of speaking have been labelled modern dialects or mainstream dialects by Peter Trudgill (1998). What most characterises them is that they are considerably more like standard English in phonology, grammar and vocabulary. The outcome of this first stage is that there are fewer differences between ways of speaking in different parts of the country - an example of dialect levelling. The second stage affects these urbanised varieties of English themselves. As anyone who travels round Britain quickly discovers, there are distinctive ways of speaking in each town and city. Sometimes these differences are quite large, and cause difficulties even for British people when they travel round. These dialects are subject to still further levelling, to such an extent that, in the south-east of England around London, it is now quite difficult to tell where a person comes from. The differences are very subtle, purely phonetic ones. EstuaryOne modern dialect - or perhaps this is an academic fiction based on several modern dialects - is so-called Estuary English. Here is David Rosewarne's description: Estuary English is a variety of modified regional speech. It is a mixture of non-regional and local south-eastern English pronunciation and intonation. If one imagines a continuum with RP and popular London speech at either end, Estuary English speakers are to be found grouped in the middle ground. They are “between Cockney and the Queen”, in the words of The Sunday Times. (Rosewarne 1994: Estuary English: Tomorrow's RP? English Today, 10[1], pp. 3-8.) Rosewarne claims that people correct their speech for reasons of social aspiration. They lose grammatically non-standard features, such as

They also, he claims, change accent. In the Southeast, they avoid the most stigmatised phonetic features, such as dropping of h and using /t/ instead of the glottal stop. The result has been the emergence of a new southern or south-eastern variety (some characteristics of which have spread to the midlands and the north). This variety, which we may call Estuary, has these features:

Paul Kerswill accepts the description but disputes the claim that this is a recent variety. He insists that something like "Estuary" has been around for longer than its commentators claim, but that in the 1990s its geographical spread has accelerated. This reflects tendencies in language change generally. It is perhaps rare for a new variety to arise suddenly and spontaneously. But one can see how a number of variant forms can slowly coalesce to represent a variety that becomes recognizable to language users - and when this happens they may adopt the features of this variety through accommodation. All descriptions of regional varieties are general and approximate - individual speakers may use all or some of them, and each to a greater or less degree, which will itself vary from one situation to another. While "Estuary English" is a loose and approximate name, the same is true of other popular names for traditional dialects, such as Cockney (supposedly spoken by people born within the sound of Bow Bells - the bells of St.Mary le Bow [Marylebone], Scouse (Liverpudlian) and Geordie (Tyneside). These popular names may also sustain inaccurate ideas. But behind these imprecise general descriptions, there are real language features that are more common in specific geographical locations. As a language student or scientist, you should look for objective evidence of this, either in published research, or in your own investigations. More recently, Jane Setter, Director of the English Language Pronunciation Unit, gave this short description of Estuary: "Estuary English is an umbrella term for a number of accents of (loosely) the South East of England which have some similar accent features. For example, varieties which come under Estuary tend to have a vocalised /l/ in syllable final position (which means /l/ is realised as a vowel similar to the one in foot, e.g. milk, apple); use glottal stop inter-vocalically and syllable finally (e.g. butter, cat), and so on. But there is actually quite a lot of difference among varieties which fall under the Estuary umbrella." Joanna Przedlacka's study of "Estuary"Vowel fronting | Glottaling | L-vocalisation Perhaps the most authoritative recent research is that of Joanna Przedlacka. Between 1997and 1999 Dr. Przedlacka studied the sociophonetics of what she calls "a putative variety of Southern British English, popularly known as Estuary English." In fieldwork in four of the Home Counties (Buckinghamshire, Kent, Essex and Surrey) she studied fourteen sociophonetic variables, looking at differences among the counties, between male and female speakers and two social classes. She studied sixteen teenage speakers, using a word elicitation task. (Dr. Przedlacka's report, Estuary English and RP: some recent findings, is available as a portable document file (PDF), while a summary, with some of the more important interpretation, is on her homepage, along with digital audio files to exemplify the speech sounds in the study.

Joanna Przedlacka compared her examples to data taken from the Survey of English Dialects (SED). She found that:

She compared the Estuary English data and recordings of RP and Cockney speakers. This demonstrated that Estuary speakers were intermediate between RP and "Cockney" as regards the incidence of t-glottaling and l-vocalisation. She suggests that this may be an oversimplification of the issue: one should also consider factors such as geographical variation or idiosyncratic characteristics of the speakers. Here are some more detailed observations from Dr. Przedlacka's research: Vowel frontingThe word blue uttered by a speaker from Buckinghamshire, has a front realisation of the vowel, while other front realisations can be heard in boots, pronounced by a Kent female and roof (Essex female). A central vowel can be heard in new, uttered by a male teenager from Essex. Back realisations of the vowel, as in cucumber, uttered by a Kent teenager are infrequent. The vowel in butter has a back realisation in the speech of an Essex speaker, but can be realised a front vowel, as in dust or cousins, both uttered by teenage girls from Buckinghamshire. GlottalingGlottaling of syllable non-initial /t/ is not the main variant in Estuary English. Here the word feet, spoken by a Kent female, exemplifies it. Realisations where the /t/ is not “dropped” are more frequent - as in bat, (Surrey speaker). Intervocalic /t/ glottaling is virtually absent from the Estuary English data. Here is one of the very few instances of it in the word forty, uttered by a Buckinghamshire female. (Here Dr. Przedlacka has a link to an audio file to exemplify the speech sound.) It is frequently found in Cockney, as in daughter, said by a teenager from the East End of London. L-vocalisationThe majority of tokens with a syllable non-initial /l/ have a vocalised realisation, as in milk (Kent speaker). Dark l, which is the usual RP realisation (as in an RP speaker's pronunciation of ankle), is also present in Estuary English, alongside clear tokens, as in pull (Essex teenager). However, clear realisations of /l/ are infrequent in the data. Joanna Przedlacka's conclusion is that "Estuary" does not correspond to anything very coherent: "The study showed that there is no homogeneity in the accents spoken in the area, given the extent of geographical variation alone. Tendencies observed include: vowel fronting, as in goose or strut, and syllable non-initial t-glottaling, which are led by female speakers. Contrary to speculation in other sources, th-fronting is present in the teenage speech of the Home Counties, the variant being used more frequently by males. Generally, social class turned out not to be a good indicator of change, there being little differences between the classes." This would tend to support Jane Setter's view, that "Estuary" is not so much a variety as an umbrella term that covers a range of accents. While she identifies them as belonging to the south east, one should also note Paul Kerswill's tracking of their movement to the Midlands and further north. Features of traditional dialectsAny dialect will yield numerous examples. These are a few: Grammar

Lexis

Phonology

Features of modern dialects that survive dialect levellingModern dialects preserve some of the features of traditional dialects. These are some of the "survivors" which have not yet been levelled out: Grammar

Phonology

Contemporary changes to modern dialectsThese are recent changes, recorded by Cheshire et al. (1989) and Williams and Kerswill (1999): GrammarUse of was in the affirmative, but weren't in the negative:

Phonology

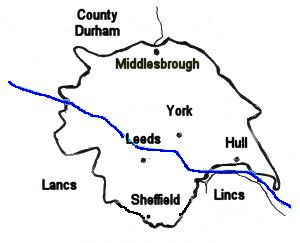

London area → Southeast: e.g., Reading, Milton Keynes → Central England (Midlands, East Anglia, South Yorkshire): e.g., Birmingham, Derby, Norwich and Sheffield → Northern England: e.g., Hull → North-east of England and Lowlands of Scotland: e.g., Newcastle, Glasgow. Paul Kerswill concludes: In sum, the outcome has been levelling: a convergence of accents and dialects towards each other. In some cases, this leads to southern features being adopted in the whole country. For other features, particularly vowels, this is not so: levelling, instead, is regional in character, usually centred on a big city like Glasgow or Newcastle or Leeds. Traditional dialect - regional variation in YorkshireI am indebted to Barrie Rhodes and the Yorkshire Dialect Society for this short description. Even allowing for the boundary changes of 1974, Yorkshire is still England's biggest county. As you might expect, there is no single Yorkshire Dialect but, rather, a variety of speech patterns across the region. What passes for “Yorkshire” in most people's imagination is, in fact, the dialect of the heavily industrialized West Riding (West Yorkshire and South Yorkshire after 1974.)

This distinction was first recognised formally at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries, when linguists drew an isophone diagonally across the county from the northwest to the southeast, separating these two broadly distinguishable ways of speaking. It can be extend westwards through Lancashire to the estuary of the River Lune, and is sometimes called the Humber-Lune Line. Strictly speaking, the dialects spoken south and west of this isophone are Midland dialects, whereas the dialects spoken north and east of it are truly Northern. It is possible that the Midland form moved up into the region with people gravitating towards the manufacturing districts of the West Riding during the Industrial Revolution. The main differences between the two areas relate to the pronunciation of certain verbs. School, for example, is traditionally pronounced “skoo-il” or “skoil” to the south and west, and “skeel” or “skale” to the north and east. Similarly, loaf, which has an almost standard pronunciation in the south and west, becomes “lee-af” or “lay-af” in the north and east, just as goose becomes “gee-as”. Perhaps the best known West Riding vowel form is the realization of o (as in hole, where southern English has the diphthong /əʊ/ ) as oi /ɔɪ/. Thus coal hole becomes “coil 'oil”. A West Riding police station is often called a “bobby 'oil”. It has to be said, though, that for most Yorkshire speakers, this isophone has now drifted northwards to the Tees. Even so, a number older speakers (particularly in the remoter parts of the Dales, the North York Moors and the Yorkshire Wolds, do still preserve some of these Old Northern vowels. One hundred years ago, however, the change would have been instantly noticeable the moment you "crossed the line". The distinction was particularly sharp at Selby, where the isophone followed the line of the River Ouse, dividing the West and East Ridings. Today, you really have to visit Durham and Northumberland to be sure of hearing younger speakers using the old northeastern forms. Other distinctions - which have survived more or less intact despite massive social change - concern words relating to specific trades and occupations. There are agricultural terms, for example, in the North and East Ridings, which are quite unknown in the West. Similarly, the mining, steel and textile terminology of the West Riding is little used in the North and East. Pockets of rhoticity (the clear pronunciation of r after vowels, which was once common to all types of English in such words as farmer and carter, but is now associated chiefly with Scotland, Ireland, the West Country and the USA) survive in parts of Yorkshire. It is still quite common in the extreme western fringes of the West Riding where it borders with Lancashire. Some older speakers in the remoter parts of the North and East Ridings are still rhotic. There probably is a "General Yorkshire" dialect now, common to the whole county, but - with care and experience - you may trace some of these fascinating variations. Lexis in traditional dialect - examples from YorkshireThe examples below are from the lexicon of Yorkshire dialect speakers. Nouns

Verbs

Many of these non-standard forms exist only in particular inflexions. There are (I think) no living verbs that correspond to maft or nither. But the past participle forms, ending in -ed, have been preserved as qualifiers in passive constructions such as Ah'm nithered and Th'art mafted, lad. For this reason I have listed them both as verbs (participles) and adjectives. This is not confusing if you see that they work very much as such familiar standard adjective/participle forms as exhausted, knackered or frozen. Adjectives

Forms like mafted and nithered come from verbs that have passed out of use. The past participle form is used adjectivally in passive constructions. Adverb

Intensifiers

Non-regional dialectsA dialect can develop or emerge in a group of speakers, which is distinctive not so much for the geographical region where they live, as some other factor. For example, the variety might emerge among

English varieties from other cultures and nationalitiesEthnic dialects | The English of black Britons | The English of British Asians Of course, the dialect arises among a community of people who spend time together - but if there is anything distinctive, in its effect on language, in the Asian cultural background of Pakistanis in Blackburn or Bradford, or in the Caribbean background of black Britons in Moss Side or Haringey, then it does not matter where in the UK those places are. Over time, and especially for later generations, then the influence of the local (traditional) dialect features will become apparent - so that there are now accents that we can describe as West Midlands Asian or Bradford Asian. It may be harder to identify regional variants of Afro-Caribbean English: while there are parts of the UK, mainly in cities, with large black populations, these are usually interspersed with white and mixed-race residents, who may be more numerous. One might also consider, say, the broad features of the English spoken in the Earl's Court district of London - where there is a large population of young Australians, living temporarily in Britain. But that might be artificial, since, in terms of their linguistic identities, these speakers have dialects from their homeland, and simply happen to be living abroad. Unless, that is, one can show that there are some features of their language that are not also found in the mother tongue Australian English they bring with them. Ethnic dialectsIn Living Language, George Keith and John Shuttleworth, refer to "Black English", in a very brief chapter. They exemplify this supposed variety with transcripts of conversation from a "British-Jamaican family" and with a prose extract and a poem from two Afro-Caribbean writers. "Black English" is a very loose descriptive label - and certainly not a uniform coherent and distinctive language variety. It is, to use Jane Setter's term for "Estuary", an umbrella, and a very large umbrella, at that, which covers a huge range of varieties. And this is true of other non-regional dialects. You may not have time or opportunity to study all of these in close detail - but you should understand the common underlying types of feature that characterize any dialect. The English of black BritonsDoes it make sense to try to locate linguistic identity, and coherent features of a language variety, in colour alone? The idea may be absurd, and perhaps offensive. If there is a recognizable black variety (or varieties) of English, how might this have arisen? As with the indigenous population, the mere existence of a language variety does not mean that it is spoken by a majority of people. Arguably, most black Britons speak more or less standard English. There are varieties which have a marked accent and special lexicon, close to some of the creoles of the Caribbean - the speakers of which are more likely to be young, male and either of a lower social class, or ideologically disposed to favour a distinctive black variety of English. We could make exactly the same observation about many traditional regional dialects of white Britons, too. There are some areas of London today, where Caribbean speech sounds are the dominant accent on social, not racial grounds - so that white teenagers will be indistinguishable from their black peers in their accent. (There is a comic example in the TV character, Ali G., the invention of the performer Sacha Baron Cohen, who is Jewish and white. But there are many real-life examples of which he is an exaggerated fictitious parody.) Lennie Henry is a black comedian whose repertoire includes various black stereotypes - but when he drops into his native accent, it is that of Dudley in the West Midlands. And in various parts of the UK, but especially in London, there are communities of black Britons identified with evangelical churches of which they form the congregations, which have very distinctive language varieties - but these varieties owe more, arguably, to the religious and devotional heritage, than to Afro-Caribbean identity. They may borrow or adopt the usages and lexicon of black churches in the USA, or those of the churches from which their forebears came in the West Indies. They may retain some features of accent that mark them as Afro-Caribbean, but may reject the special lexicon, for example, that derives from the Rastafarian persuasion. Far from depicting Britain as "Babylon" from which they want to escape, they are building the Kingdom of God here. The BBC has an Asian radio network, whereas for black audiences, it has a music network (1xtra). Here one can find examples of some varieties of black British English - as in the feature: "Are you a babyfather?" On a message board, one respondent writes: "I have nuff respect for babyfathers as well as babymothers. I came from a family where I have never seen or heard from my father throughout the whole 24 years of my life but it has not made me grow up hating babyfathers." There is a superficial use of special lexis - "nuff" for "enough", "babyfather" (absent father) and babymother (single mother). But otherwise the comment uses standard written English forms. Is babyfather a loan-word or a neologism? Another response challenges received stereotypes, with one non-standard spelling: "I feel dat this aint always true. [That black fathers are irresponsible.] I'm from Belfast and am one of the very few Jamaican families in my area and my father was always there for me goin through many struggles. I am a proud Republican/Sinn Fein voter Catholic Irish Jamaican and this is all down to my father! He taught me my history - Irish and Jamaican!" "Always there for me" is a phrase widely used by standard English speakers, after being immortalized in the theme song for the US sitcom Friends (who are culturally diverse, including two Jews, an Italian, and various Anglo-Saxon types but all white). “Dat” may indicate that the message writer begins with a wish to use an Afro-Caribbean style, but thereafter he uses standard spellings and standard English usage. The BBC 1Xtra site has a message board. Here is a posting that may seem on the surface to show a novel variety of written English: "I'm damn determined 2 av ma say on this 1 coz 2 b honest I'm fed up of music gettin all the flack 4 it. I'm not denyin that there is sum influence from music, but not UK music. Not frm uk hip hop, garage or anything else. It's a long time since I've heard a song promoting the use of guns etc. Listen 2 broken silence (so solid) and various trax fm uk garage crews and you'll hear antigun lyrix all over tha place..." Yet, if one allows for the distinctive spelling (a mixture of the conventions of text messaging and Hip Hop orthography), then this is otherwise more or less standard - in terms, that is, of grammar, lexis and meaning. It is easy for teachers to see a distinctive variety of English, favoured by young people and influential writers or poets, as representative of the speech of all black Britons - while ignoring the very large numbers whose speech is much closer to standard English or regional varieties. This attitude is encouraged by the English National Curriculum, which prescribes the study of literary works from "different cultures and traditions" (without specifying what it is from which they are meant to differ - each other, or some mainstream or traditional norm). The writers whose work pupils study includes British writers from ethnic minorities, Scots, and writers from outside Europe, who work in the English language. The latter group includes such poets as Derek Walcott, Niyi Osundare, Imtiaz Dharker and Moniza Alvi - all of whom use Standard English forms. John Agard (in the poem Half-Caste) writes in a form that approximates to a written representation of patois: Explain yuself Here we find

Keith and Shuttleworth use a similar example (a poem by the Jamaican James Berry) to exemplify literary "Black English". This seems rather to overlook the point that these writers are poets, who are also making a political statement through the use of these forms. When Mr. Agard speaks on a radio broadcast, he does not use the patois of the poems. To say that "Black English" is the patois of some poems may be tantamount to saying that the very idiosyncratic styles of James Joyce, Dylan Thomas or James Kelman are "Celtic English" (in Irish, Welsh and Scots flavours). Moniza Alvi writes in Standard English, but uses occasional loanwords - such as shalwar kameez. Sujata Bhatt also uses Standard English, but, in the poem Search for My Tongue, gives a gloss in Gujarati, using both the traditional characters and a transliteration in the Roman alphabet. It may be that the continuing use, in British Asian families, of languages from the Indian sub-continent, has made the emergence of an Asian patois less likely. And conversely, it may mean that dialect varieties will arise more naturally among communities that do not have an alternative language (whether that is Panjabi or Welsh, Gujarati or Gaelic). This will be true in mixed communities, where Asians and indigenous white people live together, and English is the common tongue. We should also be cautious about such labels as "Black English", as used by Keith and Shuttleworth. This is fine, so long as we take it to mean a variety that is characterized by non-standard forms, some of which derive from other language cultures. But we must not suppose that this, or anything like it, is the usual spoken or written language of most black people in the United Kingdom. This could lead to the emergence of language ghettos. That it has not in fact done so, especially among British Asians, may be evidence of a general wish to use mainstream and standard forms - while it is a minority who use the overt "Black" forms for artistic or political reasons. The English of British AsiansIs there anything distinctive about English as spoken or written by Asians in Britain? There is a special lexicon for, say, food, items of clothing and other things specific to various Asian cultures. The messages posted on the BBC's Asian Network message board are consistently written in Standard English - and with far fewer of the non-standard spellings that appear on the 1Xtra site (targeted at Afro-Caribbeans). The sketch show Goodness Gracious Me alludes to a dated stereotype of immigrants from the Indian subcontinent, with exaggerated accents and native idioms (specifically, it refers to the refrain of a song made by Peter Sellers and Sophia Loren to promote their 1960 film The Millionairess). The confidence of the show may come from a very successful assimilation by British Asians to the standard forms of the language. In the professions and financial services, Standard English and RP, may still be important (if not essential). So we should perhaps look to working-class communities to see whether any Asian dialect is emerging. Where there are large, less mobile, populations we might expect to see evidence of language change - and the emergence of new features or a new variety. Sue Fox has carried out research into the speech of second and third generation Bangladeshis in Tower Hamlets, in the traditional East End of London - trying to discover whether the older dialect of the indigenous population had influenced the language of this group, or vice versa. If a British Asian dialect is to emerge, this is a more likely venue than many, since it is home to the largest ethnic community (in one area) in Britain. In the whole borough Bangladeshis make up 35% of the population, but the spread is uneven, and in some wards the proportion is over 90%, while in 1998 more than half (55%) of school-age children were Bangladeshi. Sue Fox says: "I am proposing that a new dialect is emerging in this area principally from the Bangladeshi community but which is also influencing the white indigenous population, particularly white adolescent males. I believe that the historical development of the Bangladeshi settlement in Tower Hamlets provides us with clues as to how this new variety has evolved and would not like to suggest that it has come about through some kind of conscious [or subconscious for that matter] dissent to the standard variety." Sue Fox has not yet published her findings - they will appear here when they are available. The armed servicesThe armed services are unusual, in that the families of service personnel, and especially the children, spend much of their lives as a closed community, physically isolated (by security fences and armed sentries) from the ordinary residents of the area where a base or barracks is located. And the families are transient from one base to another, both within and outside the United Kingdom. Since the service personnel share the same occupation, the common knowledge of this occupation among the families is greater than in other communities - though historically one would have found something similar in areas dominated by a single form of employment or industry. The armed services have a huge special lexicon both of terms common to all the services, and of others distinctive to one. Outsiders are in Civvy Street (where soldiers, sailors and airmen go when they leave the service). In all the services, one shops at the NAAFI (Navy, Army and Air Force Institute), and takes leave (holidays). Service personnel are posted to a new location. Their relations can fly to join them at no expense on an indulgence flight, provided by Transport Command of the RAF. In the Royal Air Force, cadets are sprogs and military police are Rock Apes (an insulting comparison of the unskilled police - unlike other RAF personnel they do not have a trade - to the wildlife of Gibraltar); angels measure altitude (each is 10,000 feet), a bandit is an enemy aeroplane and a bogey is an unidentified aircraft, while airspeed is measured in knots - nautical miles per hour. Here is a small selection of terms from Jackspeak - as used by service personnel in the Royal Navy. (I am grateful to Fiona Kerr, for these examples.)

Why do dialects differ?I am grateful to Barrie Rhodes and the Yorkshire Dialect Society for this short account. Sometimes languages break down into dialects as populations spread over larger areas. However, it is often the people who move farthest away from their "homeland" who preserve the older patterns of speech. American English, for example, still has many words (such as "gotten"), which were once common in England. Similarly, we still pronounce the letter W in the Old English way, but in most other Germanic languages it now sounds like our V. (The modern German for "warm" is spelt the same as in English, but pronounced "varm"; in modern Norwegian, the cognate adjective is spelt "varm" and pronounced with the vowel /ś/, rhoticized by articulation of the r sound, or r-colouring.) Also, new waves of settlers, such as the Vikings, bring in words, phrases and grammatical forms which are then adopted by the natives, simply so they can communicate with the newcomers. Very often, the dialect spoken by the richest or most powerful section of the population gradually takes over and becomes the "standard" language of a nation. This is certainly true of English, where the speech used in the triangle of land between London, Oxford and Cambridge eventually became what we now call "Standard English". "Standard English" is still a dialect, but is based more on social class rather than on region. Sometimes newcomers adopt words from older, native languages. The English spoken in the Welsh Borders is partly influenced by Welsh itself. Also, the Vikings who settled in the North West of England came via Ireland, where they had already learned some Gaelic. Consequently, there have been Irish words in Lancashire speech since long before the victims of the Irish potato famine settled there in the 1840s! Other variations are harder to explain. Seven hundred years ago, we went to sea in "boots" and wore "boats" on our feet. Then something happened to the way “O” was pronounced, and boots became boats! Similar changes affected other European languages at about the same time (the Great Vowel Shift) but nobody is quite certain why. Some English dialects, such as Geordie, still use the older form. (So in Newcastle blackboards fly and lay eggs ...or, rather, blackbirds do!) Until about 1700, most English speakers (whatever their dialect) pronounced the letter r very clearly in words where it followed a vowel, such as in "farmer" and "carter" (this is known as rhoticization). After 1700, this pronunciation died out quite rapidly and is now virtually unknown in Standard English. It survives, however, in the dialects of the West Country, part of Lancashire and some parts of Yorkshire. It is also a standard feature of Scots, the English spoken in Scotland. It is also found in Ireland, and much of North America. Nobody is quite sure why it disappeared from Standard English, but its loss was certainly noticed at the time. Some eighteenth-century folk complained about "R-dropping" the way people complain about "H-dropping" today! Sometimes a particular accent or dialect simply becomes fashionable, and other people start to copy it. It is said that the speech of young people today is being influenced by Australian TV programmes. Similarly, the tendency to pronounce -th as f (as in think = fink) which was once almost unknown outside London, is now quite common as far west Bristol ... but only amongst teenagers and children. Only time will tell if these changes spread or stick. Dialect is not disappearing, but it is always changing. Where to find out moreText-books | other print publications | Research reports | Web sites Text booksMany text books published for school students have only a very brief section on dialect. Shirley Russell has a long and useful section in Grammar, Structure and Style (1993; Oxford) - see pages 139 to 168. Howard Jackson and Peter Stockwell have a shorter, but informative, section in An Introduction to the Nature and Functions of Language (1996; Stanley Thornes) - see pages 118 to 125. Chapter 20 of Professor Crystal's Encyclopedia of the English Language (1995; Cambridge) is entitled Regional Variation. There is an extensive section on British dialects starting with Variation in British English (p. 318), and continuing with articles on English dialects in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. Other print publicationsThe Yorkshire Dialect Society has produced an excellent Information and Resource Kit for Teachers entitled Dialect Studies in Schools. If you are a teacher and would like a copy, please contact Barrie Rhodes by e-mail to docpop@tiscali.co.uk Research reportsI am grateful to Joanna Przedlacka and Joanna Ryfa, who have allowed me to publish copies of their research papers here. Click on the links below to open the papers in portable doucment format (pdf). You need pdf reader software, such as Adobe Reader, to view the documents. Click here to get a copy of the free Adobe Reader software.

Web sites

© Andrew Moore, Barrie Rhodes and the Yorkshire Dialect Society, 2003-2004; universalteacher@bigfoot.com

|

The Humber-Lune line (blue on the map)

The Humber-Lune line (blue on the map)